1. Introduction. — 2. The concept of platform employment in Kazakhstan. — 3. The obligation to conclude an employment contract when hiring: an analysis of the current legislation and judicial practice. — 3.1. Employee performance (labour function) according to a certain qualification, specialty, profession or position. — 3.2 Fulfillment of obligations personally with submission to the labour schedule. — 3.3 Receipt of wages by the employee. — 4. Problem statemont. — 5. Methodology. — 6. Conclusions.

ABSTRACT

Background:The article is devoted to the main issues of legal regulation of platform employment in the Republic of Kazakhstan. The authors gradually considered the issues of the overarching concept of platform employment, its national legal regulation, the correlation of platform employment with labour relations, and the necessity of mandating Internet platform operators to conclude employment contracts with individuals providing their services.

Methods:In the process of analysing the current Kazakhstani labour and related legislation, national and international judicial practice, the authors came to the conclusion that the Social Code adopted in 2023 and the Law ‘On Online Platforms and Online Advertising’ separate the concept of an Internet platform and online -platforms. Internet platforms are so-called work platforms that specialise in mediating the provision of services and work performance. The authors identified several problems that arose with adopting the Social Code. In particular, the authors do not share the legislator’s idea on the need for civil law regulation of relations in platform employment between the contractor and the Internet platform operator. The authors propose a targeted approach to determining the nature of the legal regulation of platform employment. Labour activity using Internet platforms, if it has signs of hidden labour relations specified in the ILO recommendations, should be regulated by labour legislation. Otherwise, the trend towards precarisation of the Kazakh labour society will inevitably strengthen.

Results and conclusions:Based on the statistical data analysis, the authors concluded that more and more people with higher or professional education adjoin the number of self-employed, hence the performers of platform employment. The data suggest that precarisation in the Republic of Kazakhstan is rapidly spreading among the underclass labourers and the relatively prosperous and promising able-bodied population of the country.

1 INTRODUCTION

Until mid-2023, the Republic of Kazakhstan (hereinafter referred to as the RK) had no legislative framework to regulate platform employment—drivers and couriers of the most common Internet platforms in the country, such as Yandex. Taxi, Volt, Glovo, Chokofood and Indriver operated as individual entrepreneurs. The relationship between the platform owner, the courier/driver and the client arose based on a public offer and was regulated by civil law. Internet platforms acted as intermediaries between customers and service providers, including taxi drivers, couriers, and, occasionally, taxi companies. Relations between the owners of online media and executors of orders were not regulated within the framework of labour relations; accordingly, the obligation of owners of Internet platforms to conclude an employment contract with drivers and couriers when hiring was absent. When hiring, the commitment to terminate an employment contract determines the regulation of relations between the parties to labour relations by labour legislation.1 The labour legislation of the RK guarantees employees the right to work, the exercise of labour rights (the right to rest, safety and labour protection, payment for downtime, compulsory social insurance, guarantees and compensation payments, etc.), and the protection of labour rights (the right to strike, judicial protection, conciliation commissions, association in trade unions, etc.). In addition, labour legislation provides for state control over its observance. This oversight is carried out through the Institute of State Labour Inspectors, who have the authority to check employers for employee labour rights violations, issue orders to eliminate violations, and initiate administrative or criminal liability.

The lack of labour rights and minimum social guarantees among couriers and taxi drivers operating through Internet platforms gave rise to a wave of discontent, which later turned into strikes and rallies.2 On January 17, 2023, the Ministry of Finance of the RKlaunched a pilot project on the application of a different tax administration procedure for persons providing services using Internet platforms (hereinafter referred to as the Pilot Project), set to be implemented by the end of 2023.3

Under this draft, Internet platform owners, referred to as ‘operators of Internet platforms’, would become tax agents responsible for deducting personal income tax (PIT), mandatory pension contributions (MPC), social contributions (SC), mandatory health insurance contributions (MHIC) from the income of the service providers. Thus, the measures of the state to impose the obligation on the owners of Internet platforms (operators of Internet platforms) to withhold the above deductions to the budget, on the one hand, contribute to the provision of certain social guarantees to persons providing services and carrying out work using Internet platforms. Thus, the above-mentioned persons are subject to health insurance; they are charged a pension. On the other hand, government measures still need to fundamentally change the current situation with the lack of labour rights for couriers and taxi drivers working through Internet platforms.

On April 20, 2023, the Social Code of the RK,4 as well as amendments and additions to the Labour Code of the RK5 concerning the legal regulation of platform employment, the specifics of the legal law of the labour of employees of Internet platforms. Thus, the Social Code of the RK defines platform employment; an Internet platform represents the circle of subjects of platform employment (the operator of the Internet platform, contractor, customer) and, most importantly, indicates that relations between subjects of platform employment should be regulated within the framework of civil law, thus putting an end to the disputes about platform employment as a type of labour activity or civil legal activity for the provision of services and the performance of work. Employment relations can only arise for contractors who independently act as employers, with employees involved in providing services and performing work using platform employment. For example, a taxi company with a staff of drivers working under an employment contract acts as a performer.

In connection with this, several problems arise that are left unresolved and even exacerbated by the provisions in the Social Code of the RK and the novelties of the Labour Code of the RK. These issues fail to address the problems at hand and contravene international and constitutional norms. For instance, the presence of ‘hidden forms of labour relations’ in the RK, which is discussed in ILO Recommendation No. 198,6, is not eliminated by conducting an effective national policy to combat such a negative phenomenon, but on the contrary, is legalised with the enactment of the Social Code of the RK, despite judicial practice, both international and domestic. The article analyses international jurisprudence on labour disputes related to work through Internet platforms. It is an example from the domestic jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of the RK.7 Many court decisions reviewed establish a hidden employment relationship between couriers/taxi drivers and Internet platform owners. Despite this, in the RK, the obligation to conclude an employment contract when hiring performers — natural persons of platform employment is not fulfilled.

One of the reasons for the absence of a requirement for Internet platform owners to conclude employment contracts when hiring, in addition to the rule-making decisions of the state, lies in the general trend of narrowing the impact of labour law on labour activity in the RK, accompanied by the expansion of civil law elements within the employment relationships. An example of this trend is the presence in the Labour Code of the RK, which acknowledges the existence of multi-party employment relationships.

In addition, the problem of the absence of obligation of owners of Internet platforms to conclude an employment contract with individuals is closely related to the issues of the place, role and future of labour relations in the modern digital society. On the one hand, the digital economy contributes to the development and positive modification of labour relations; on the other hand, ignoring the basics of labour law and the reasons for its occurrence can lead to mass precarisation of Kazakhstani society.

2 THE CONCEPT OF PLATFORM EMPLOYMENT IN KAZAKHSTAN

In accordance with paragraph 1 of Article 102 of the Social Code of the RK, platform employment should be understood as the type of activity for providing services and the performance of work using Internet platforms and (or) platform employment mobile applications. An Internet platform is a resource intended for interaction between the operator of the platform, the customer and the contractor for the provision of services and performance of work (clause 81, clause 1, article 1). The legislator defines a platform employment mobile application as a software product installed and launched on a cellular subscriber device and providing access to services and works provided through an Internet platform (clause 126, clause 1, article 1).8

It should be noted that the concept of an Internet platform in the RK is inherent only in platform employment. The Law of the RK ‘On Online Platforms and Online Advertising’,9 an online platform is defined as an internet resource and (or) software operating on the Internet, and (or) an instant messaging service. This definition encompasses functions related to receiving, producing, posting, distributing, and storing content on the online platform by the platform’s users through their registered account or within a public community. It is worth noting that this definition excludes Internet resources and (or) software operating on the Internet, as well as instant messaging services designed to provide financial assistance and e-commerce. Even though, by their nature, the words ‘online’ and ‘internet’ have almost the same, if not identical, meaning, the legislator distinguishes the concept of ‘internet platforms’ from the general circle of platforms operating via the Internet.

The distinctive characteristics of an Internet platform, which make it possible to distinguish it from other online platforms, include 1) mediation to provide services and perform work and 2) mediation between a unique, strictly defined circle of subjects of platform employment.>.

Mediation to provide services and perform work is a vital aspect of the concept of not only an Internet platform but also platform employment since it indicates the essence and content of the idea of employment as a labour activity. Thus, the legislator clearly distinguishes between online platforms for leisure, placement, storage, transmission of information, provision of services (financial services, e-commerce, Internet banking, etc.) and Internet platforms of platform employment, through which customers-users are provided services and certain works are performed. For example, through the Glovo Internet platform, the customer places an order for a certain product (certain food, drinks), and he is provided with a service for ordering and delivering it; at the same time, the restaurant that accepted the order makes a dish for a specific customer, i.e. e. performs specific work. At the same time, the Yandex Internet platform, used for passenger transportation, mediates the provision of taxi services without performing specific work. Nevertheless, in our opinion, the main thing is the implementation by the parties of platform employment of labour activity through the provision of services and the performance of work.

Through the Internet platform, unlike any other online platform, mediation is carried out between the operator of the Internet platform, the customer and the contractor.

The operator of an Internet platform is understood as an individual entrepreneur or legal entity providing, using the Internet platform, services for the provision of technical, organisational (including services involving third parties for the provision of works or services), information and other opportunities using information technologies and systems for establishing contacts and concluding transactions for the provision of services and performance of work between contractors and customers registered on the Internet platform. In other words, Internet platform operators provide intermediary services to customers and contractors through Internet platforms. At the same time, for platform employment, it does not matter who owns the Internet platform as an Internet resource who owns it. The Law of the RK ‘On Online Platforms and Online Advertising’ contains the concept of an owner of an online platform as an individual and (or) legal entity with the right to own the online platform.

The content in the definition of platform employment of such elements as an online platform and a mobile application of platform employment is not entirely explicit, as mutually exclusive terms. So, in implementing platform employment, in one of the cases, either an Internet platform or a mobile application of platform employment is used. However, their definitions regarding platform employment mention only the Internet platform. So, the customer is a natural or legal person registered on the Internet platform and placing an order on it to provide services or perform work. Contractor — an individual, individual entrepreneur or legal entity registered on the Internet platform, providing services to customers or serving work using the Internet platform based on a public contract. In this case, if orders are made only through the platform employment mobile application, does the operator of the Internet platform, as well as other subjects of platform employment, participate in the process of providing services and performing work? We consider the indication in the definition of platform employment of a mobile application of platform employment to be redundant, leading to a complication of the concept of platform employment. Since the mobile application of platform employment in the Social Code of the RK is referred to as a software product that provides access to services and work provided through the Internet platform, it would be more appropriate to make the following changes and additions to the Social Code of the RK. It is proposed to supplement paragraph 1 of Article 102 of the Social Code of the RK and state it as follows:

‘Platform employment is an activity for providing services or performing work using Internet platforms. Access to services and works provided through the Internet platform can be carried out through the mobile application of the platform employment’.10

An important factor characterising platform employment in the RK is the civil law regulation of relations between the subjects of platform employment. According to paragraph 3 of Article 102 of the Social Code of the RK, the relationship between the operator and the customer, as well as the contractor, is regulated by the Civil Code of the RK (General and Special parts).11

However, clause 3 of Article 102 of the Social Code of the RK does not indicate which specific civil law contracts regulate separately the relationship between the operator of the Internet platform and the customer, the operator of the Internet platform and the contractor, the customer and the contractor, or there is a tripartite agreement between the parties to platform employment. Under subclause 3, clause 2, article 102 of the Social Code of the RK, the contractor provides services to customers or performs certain work based on a public agreement.

According to Article 387 of the Civil Code of the RK, a public agreement is an agreement concluded by a person engaged in entrepreneurial activities and establishing his obligations to sell goods, perform work or provide services that such a person, by the nature of his activity, must carry out in relation to everyone who contacts him will turn.

The difficulty is that a public contract is traditionally a bilateral contract, where the entrepreneur is the executor and initiator of such an agreement. In the case of platform employment, the initiator of the public contract is the Internet platform. The contractor and the customer have the right to accept the terms of the public contract of the offer or not to accept or refuse the services. The contractor and the customer are on equal terms. In addition, as a rule, two types of public offer contracts function in conjunction with the customer-operator-executor. The first is between the Internet platform operator and the contractor; the second is between the operator and the customer. By and large, there is no such agreement between the contractor and the customer. For example, when ordering taxi services through the Yandex Internet platform, the customer agrees to the terms of Yandex, the Internet platform operator, and the contractor is not involved in this process in any way. The contractor and the Internet platform operator have a separate agreement; the customer does not have the right to agree, disagree, or relate to this agreement in any way. In this regard, we consider it necessary to develop a separate platform employment contract similar to the Staffing Agreement, which will spell out the legal status of the Internet platform operator concerning both the contractor and the customer, the obligations of the Internet platform operator, as well as the responsibility of the operator Internet platforms in front of the customer and the contractor.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) highlights the following features of platform employment: — paid work is organised through online platforms; — three parties are involved: online platform, worker and client; — results are concluded under the contract; — tasks are divided into functions; — Services are available upon request.12

Platform employment in the RK, in addition to the above, has its characteristics:

- The provision of services and the performance of work is carried out through the mediation of Internet platforms;

- There is a unique range of subjects of platform employment;

- Relations between the subjects of platform employment are regulated by civil law and are based on a public offer contract;

- A wide and indefinite range of obligations of operators of Internet platforms;

- The need to create a uniform agreement in platform employment between its subjects.

3 THE OBLIGATION TO CONCLUDE AN EMPLOYMENT CONTRACT WHEN HIRING: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CURRENT LEGISLATION AND JUDICIAL PRACTICE

According to paragraph 2 of Article 23 of the Labour Code of the RK, the employer is obliged to conclude an employment contract with the employee when hiring.13 Such an obligation on the part of the employer is necessary in order to exclude the substitution of labour relations with other types of social relations, mainly civil law, in order to prevent the emergence of so-called ‘hidden labour relations’ in society.

The ILO recommends distinguishing the following features of an employment relationship: performance of work in accordance with the instructions and under the control of the other party; integration of the employee into the organizational structure of the enterprise; performance of work in accordance with a certain schedule; if such work requires the presence of an employee; when it is supposed to provide tools, materials and mechanisms by the party that ordered the work; periodic payment of remuneration to the employee; the fact that this remuneration is the sole or primary source of income for the employee, etc.14

The Labour Code of the RK makes it possible to distinguish an employment contract from other types of contracts on the basis of the following features: 1) performance by an employee of work (labour function) for a certain qualification, specialty, profession or position; 2) fulfillment of obligations personally with subordination to the labour schedule; 3) receipt by the employee of wages for work (Article 27). At the same time, the condition that relations under an employment contract are determined in the presence of at least one of the three signs specified in Article 27 of the Labour Code of the RK is seen as important. We propose to consider each of them.

3.1 Employee performance (labour function) according to a certain qualification, speciality, profession or position.

The Labour Code of the RK does not explicitly define qualifications, speciality, profession, or position. However, some terms are found in other legal acts. So, according to paragraph 5.8 of Article 1 of the Law of the RK, ‘On professional qualifications’,15 a profession is understood as an occupation carried out by an individual and requiring specific qualifications for its implementation. Instead of qualification, the concept of professional qualification is used — the degree of professional training that characterises the possession of competencies required to perform labour functions in the profession. Competence — the ability to apply skills that allow you to perform one or more professional tasks that make up the job function. According to the Classifier of professions and specialities of technical and vocational, post-secondary education (GK RK 05-2008),16 a speciality is a complex of knowledge, skills and experience acquired through targeted training necessary for a certain type of activity, confirmed by relevant education documents. There is a concept of public office, official powers, official.17 The unifying factor of the above concepts is that they are all interconnected with labour activity and sometimes directly follow from it. This does not give grounds to assume a causal relationship between these concepts and the identification of labour relations. Thus, the civil service itself is a part of labour relations regarding certain categories of workers. It would never occur to anyone to doubt that work in the public service can be formalised as a civil law contract. As for other labour activities, the concept of a profession, speciality, or qualification directly indicates the obligatory presence of appropriate education, a document confirming its presence. For example, if a person gets a job in a medical institution with a proper medical diploma, the likelihood that relations with such an employee will be formalised through a civil law agreement to provide services or a work contract is minimised. The situation is not so clear when it comes to professions such as a taxi driver or a courier. It is necessary to distinguish the work of a courier and a taxi driver working through Internet platforms from taxi drivers and couriers operating under an employment contract, whose activities are regulated by other legislative acts. So, according to the Law of the RK ‘On Post’,18 a courier is an employee of a mail operator or an individual who has an agreement with a mail operator who accepts a registered postal item from the sender outside the production facility and hands such item to the addressee or sender at the specified address on the postal item. According to the Rules for the Carriage of Passengers and Luggage by Road, a taxi driver is an employee of a taxi company and has certain obligations, for example, the obligation to undergo a medical examination.19 In addition, when applying for a job, taxi drivers must have an appropriate driver’s license, indicating the presence of certain driving skills, driving experience, etc.

Regarding couriers and taxi drivers working through Internet platforms, the Social Code of the RK defines them as contractors providing services and performing work under a public contract. However, it is not entirely clear why the work of a courier at the post office or a driver of a taxi fleet is a profession associated with the presence of a position, while the same work conducted through Internet platforms is characterised as either individual entrepreneurship (running a business) or lacks a specific legal status altogether. In this regard, it is not entirely accurate to characterise all individuals as potential performers. In contrast, in practice, only individual entrepreneurs can legally be taxi drivers and couriers working using Internet platforms. The Entrepreneurial Code of the RK defines entrepreneurial activity as an independent, initiative activity aimed at obtaining net income through property, production, sale of goods, performance of work, and provision of services based on the right of private or state property.20 Obviously, couriers and taxi drivers working through Internet platforms are not engaged in entrepreneurial activities and do not conduct independent business.

This situation aligns with the perspective of the Court of Appeal of Australia,21, which examined the case of Amita Gupta, a delivery driver for Uber. The Court concluded that Ms. Gupta did not run a business with the usual hallmarks of a business. In some cases, as the Court of Appeal points out, the above fact may favour the conclusion that a person is an employee. In other cases, it may support the conclusion that the person is an independent contractor. The Court of Appeal ruled that the fact that the plaintiff did not run a business did not indicate that she was an employee or a contractor. According to the Australian Court of Appeal, Ms Gupta worked for herself.

The Social Code of the RK indicates that in addition to individual entrepreneurs, persons ‘working for themselves’ are employees working under civil law contracts and independent workers. The independent workers category comprises payers of a single aggregate payment,22 mainly small traders and artisans who provide services exclusively to individuals. Employees who do not work under employment contracts are classified as high-risk. If employees working through a staffing agreement are more or less protected by the labour legislation of the RK, then the rest fall into the category of ‘hidden labour relations’. In this case, there is a tendency for the status of performers in platform employment to be ambiguous. In our opinion, Yandex taxi drivers, for example, cannot be considered business people because they are isolated from contact with potential customers.

As an alternative example, let us consider drivers working through the Internet platform InDriver. In this setup, customers initiate ride requests through a mobile application or an Internet platform, specifying the amount they are willing to pay for their trip. These ride requests are then displayed to the drivers, who, in turn, decide to accept the order out of their own autonomy. Additionally, the driver can offer a different fare for which they are willing to provide the service. Customers are afforded less than a minute to accept or refuse the offer.

In contrast, Yandex-taxi, as the operator of the Internet platform, determines the trip’s price and route. The contractor cannot interact with the customer, and the customer cannot choose a specific contractor.

Thus, from the above, we can conclude that for those professions and types of work that do not require higher education or certain special skills (with the exception of taxi drivers), labour relations are primarily established through a direct formal instrument — an employment contract. The nature of these professions does not inherently create the employment relationship; rather, it is structured through this legal agreement. In the case of taxi drivers, they remain taxi drivers, but when working in a taxi company, their profession aligns with traditional employment. However, when they work through an Internet platform, they work for themselves, as independent contractors. Interestingly, the Social Code of the RK, in our opinion, introduced a new criterion (platform employment), which determines the difference between labour and civil law relations.

3.2 Fulfillment of obligations personally with submission to the labour schedule.

According to the Labour Code of the RK, the labour schedule regulates relations for organising the work of employees and the employer. The concept of work schedule is closely related to labour discipline. Considering the issues of labour discipline in enterprises, G. Clark pointed to the coercive and coordinating nature of work discipline.23 In our opinion, labour discipline, like the work schedule, combines coercion and coordination of labour processes. According to paragraph 2 of Article 63 of the Labour Code of the RK, labour regulations establish working hours and rest periods for employees, conditions for ensuring labour discipline, and other issues regulating labour relations. Platform employment does not provide for a clearly fixed work schedule; the Internet platform operator does not set a work schedule, the contractor can work on weekends and holidays, etc. The free work schedule does not allow identifying platform employment as an employment relationship. This is also indicated by international jurisprudence.24 The Labour Code of the RK provides flexible (variable) working hours, during which employees can perform labour duties at their own discretion. On the one hand, an employment contract is an agreement providing for the equality of the parties, and in this regard, it would seem that there should be no difference between an employment contract with flexible working hours and a civil law platform employment contract for the provision of services and work. On the other hand, a flexible schedule is part of the work schedule, where the employee is in a subordinate position in relation to the employer, while platform employment does not provide for subordination. However, it is important to understand that each work through the Internet platform has its own characteristics and difficulties in a uniform approach. So, if taxi drivers or couriers with vehicles can afford to violate the established norms of working hours relatively without harm to health (i.e. work at night, around the clock, etc.), then food couriers, as a rule, work a certain amount of time, according to the same schedule, which makes their work indistinguishable from work under an employment contract. In addition, the work schedule issue when working with Internet platforms is not unambiguous. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court points out that an Uber driver’s job is under the direction and control of the Internet platform operator, noting that control is less about approving or directing the end product of the job than controlling the means to achieve it.25 A similar position is taken by the Belgian court, drawing attention to the fact that the way drivers organise their work trips with platform employment can in no case depend on a direct dialogue between the driver and their passenger.26

It should also be noted that the principle of personal performance by an employee of a certain work, as one of the signs of delimiting labour relations from civil law, with the introduction of the concept of joint employment into the Labour Code of the RK (paragraphs 56-1, paragraph 1, article 1), is gradually being neutralised. We believe that the institution of joint employment directly contradicts the concept of labour relations, an employment contract. It is not entirely clear the decision of the legislator to introduce joint employment without comprehending such an institution of labour law as the disciplinary liability of an employee.

Thus, the fulfilment of obligations personally with subordination to the labour schedule is inherent in both platform employment and labour relations, despite the debatable nature of this problem. In most cases, the distinction between the work of platform employment and work under an employment contract is largely conditional and depends upon the state’s interpretation and assessment value of labour relations.

3.3 Receipt of wages by the employee.

The Labour Code of the RK understands wages as remuneration for work, depending on the qualifications of the employee, the complexity, quantity, quality and conditions of the work performed, as well as compensation and incentive payments. The Labour Code of the RK, in addition to the traditional monthly wage, provides for hourly wages for the time actually worked by the employee. The concept of an employment contract implies that wages are paid by the employer, while in platform employment, earnings come directly from customers, and the amount of earnings depends on the number of customers and is not a fixed amount. So, it is not possible to talk about the presence of such a sign of labour relations as wages with platform employment. Nevertheless, we believe that the signs of labour relations specified in the Labour Code of the RK require an extensive interpretation. In particular, we consider it necessary to add an indication of the only source of income to the criterion of the availability of remuneration for work in the form of wages paid by the employer. In this regard, the practice of the Supreme Court of the RK.27

At the end of 2021, the Supreme Court of the RK considered a cassation appeal to review the decision of the Judicial Collegium for Administrative Cases of the Astana City Court in a civil case. The case pertained to the claim brought forth by Ospan A. against a private bailiff (PB) named Astana Sarbasov M. The claim was centred on the demand to remove an arrest placed on the debtor’s account. Initially, the court ruled in favour of the plaintiff, stating that the arrested PB’s account received payment for courier services, which, in turn, were Ospan’s only source of income. However, the Court of Appeal later annulled the above decision and issued a new one, dismissing the claim. The Court based its rationale on the fact that Ospan was not in an employment relationship with LLP ‘Glovo Kazakhstan’ but only operated based on an agreement on accession to the conditions for providing services by courier.

Based on the terms of this agreement, Ospan received remuneration for his services rendered based on the volume of services he provided, which could be paid in both cash and non- cash form. After examining the bank account statements, the appellate court concluded that at the address of Ospan from LLP ‘Glovo Kazakhstan’, no payments were received, and remuneration or wages were not transferred. The plaintiff also failed to provide exhaustive evidence demonstrating that the money transfers and receipts took place from LLP ‘Glovo Kazakhstan’. Consequently, the working capital in Ospens’s account could not be classified as remuneration or wages for services rendered.28

The Supreme Court of the RK saw in the relationship between the courier Ospan and LLP ‘Glovo Kazakhstan’ the presence of ‘hidden labour relations’. Thus, the Supreme Court of the RK pointed out that, despite the fact that the systematic payment of remuneration by LLP ‘Glovo Kazakhstan’ could not serve as a sufficient basis for the presence of labour relations, however, based on the requirements of international acts,29 the Court of Appeal did not take into account the fact that the income from courier work was the only source of income for Ospan. This fact was substantiated by Ospen’s financial statements and bank records, which were presented to the court and attached to the materials of the administrative case, as well as payment orders of the organisation and information from the database ‘Pension contributions’.

We believe that the concept of wages, as a criterion for distinguishing labour relations from civil law relations in the RK, should not be limited to the framework of the remuneration given by the employer. In our opinion, it is necessary to apply the recommendations of the ILO and consider whether the payments of operators of Internet platforms are the only source of income for the contractor.

Thus, the obligation of the Internet platform operator to conclude an employment contract with platform employment workers arises only if the platform employment relationship has signs of a ‘hidden employment relationship’. Such signs of labour legislation and judicial practice relate to the personal performance of work according to a certain qualification, speciality, profession or position, with subordination to the labour schedule, and payment by the employer of wages for work. In the RK, there is a positive practice of the Supreme Court of the RK on the recognition of platform employment as a ‘hidden labour relationship’. At the end of 2021, the Supreme Court of the RK sent a private ruling to the Minister of Labour and Social Protection of the Population of the RK,30 in which he ordered the Minister to pay attention to the revealed facts of the presence of ‘hidden labour relations’ and exercise appropriate control and supervision in the field of detection and suppression of ‘hidden labour relations’. The Supreme Court of the RK, addressing the Minister, pointed out the need to work out issues to improve the current legislation in the spirit of bringing national standards for the protection of labour rights and regulation of labour relations closer to the standards of the most developed countries to harmonise labour legislation. However, the legislative policy of the RK recognised the autonomy of platform employment, which, in our opinion, prematurely excluded the presence of ‘hidden labour relations’ in platform employment and recognised platform employment workers as self-employed persons. In connection to this, it seems necessary to consider global and domestic trends in understanding the general theory of labour relations, the role of labour legislation and its relationship with platform employment.

4 PROBLEM STATEMENT

G. Davidov offers several likely reasons for identifying and formulating justifications for the functioning of labour legislation. In particular, the author highlights the need to ask about the ultimate goal of reforming labour legislation and adapting it to new realities and challenges. At the same time, the idea is voiced that the improvement of labour legislation, depending on the goal, is due to a radical transformation of the labour system.31 In this regard, the legislation on platform employment in the RK is emerging at the intersection of rethinking the foundations of labour relations, understanding labour in modern society, the dilemma of the need for labour legislation to adapt and change according to the requirements of the digital economy or be replaced by new, more flexible employment systems.

The classical understanding of labour relations is associated with the axiom that there is an inequality in bargaining power between the bearer of power — the employer and those who are not the bearer of power — wage workers. In such conditions, the labour law and legislation system acts as a compensatory force to counteract inequalities in negotiations between the parties to labour relations. According to A. Hyde, labour laws in modern advanced economies are a means to achieve concessions from elites in response to organised, sometimes destructive, worker discontent.32 It should be noted that the ‘concession’ approach is not typical for all countries. Thus, the approaches of the so-called ‘capitalist’ and ‘communist’ countries to define labour relations, labour law and legislation differed in their time. Although after the collapse of the USSR, the policy of the RK in the field of labour relations has undergone a number of changes associated with the departure from the command and administrative mechanism of legal regulation of labour to market methods, the role of the state, as a kind of ‘arbiter’ between the employee and the employer, has remained unchanged. In connection to this, the image of an employee as needing protection against the backdrop of an underdeveloped trade union movement in the RK is not unfounded. At the same time, the constitutional principle of freedom of labour by introducing a civil law mechanism for regulating certain aspects of labour relations creates an inevitable tendency to understand the role of labour not through the classical model of labour relations but through the institution of employment. Gradually, there is a growing awareness that employment regulation plays a complex and multifaceted role through which major societal transformations can be observed.33 While the canons of classical labour relations are ‘weakened’, the possibilities for strengthening and multiplying this traditional connection of subordination and control are expanding.34 According to H. W. Arthurs, ‘labour’ is no longer perceived as a movement, class, or significant area of public policy. At the same time, workers prefer an alternative identity: consumers and investors rather than producers.35 B. Langille indicates that normative basis labour rights must be based on the regulation of the deployment of human capital, not confined to preventing unfairness in the negotiation of contracts.36 The legitimisation of efficiency as one of the main objectives of labour law is part of a broader trend in which an early focus on job protection is gradually replaced by a commitment to liberal market ideals of flexibility, competitiveness and profitability.37 Nevertheless, recent monographic studies show that the study and analysis of platform labour activity are impossible without considering the relationship between labour and value. This would require a transition from a comprehensive view of the functions performed by platforms to the idea of conflict occurring within platforms.38

The types of conflicts and problems that occur within platforms, as we ll as generated by work platforms, are diverse. One of the main problems of working platforms, in our opinion, is the uncertainty of the position and legal status of persons working with the mediation of Internet platforms and the consequences arising from such a situation. For example, platform workers in the workplace and online face a wide range of health and safety issues in the workplace.39 Studies have been conducted on the impact of the gig economy platform employment on workers’ health.40 Recent scientific works testify to the growing trends of unobtrusive dehumanisation of society, the deterioration of the general condition of workers in atypical employment and the example of employees working with online platforms.41 Some researchers, despite the advantages of working in the gig economy, point to the existing problems of the lack of social protection provided by traditional employment contracts.42 Thus, the range of the above problems, in our opinion, is directly related to the fact that the uncertainty of the status of persons working through Internet platforms entails general instability and the prerequisites for the formation, both in the world and in the RK, of a hidden form of precariat.

G. Standing believed that the precariat is made up of many insecure people living indefinite, uncertain lives, working in random and constantly changing jobs with no prospects for professional growth.43 The above description of the precariat as a social phenomenon brings it closer to the concept of underclass labourers, which include the unemployed, especially vulnerable segments of the population, marginalised individuals with extremely low earnings, etc. However, in our opinion, in the wake of the spread of labour activity using Internet platforms, performers of platform employment in the RK can also be attributed to the precariat for several specific characteristics. These include lack of labour rights and guarantees; irregular work schedule; indefinite wages; business risks; lack of influence on the scope of their activities, the amount of profit; low wages; lack of necessary conditions for the implementation of labour activity; disproportion of risks with wages; the public nature of the contractual relationship between the contractor and the operator of the Internet platform, etc. The Social Code of the RK, amendments and additions to the Labour Code of the RK, together with the Pilot Project, artificially brought the performers of platform employment into the category of self-employed — individual entrepreneurs who are traditionally considered to be more prosperous than the rest of the self-employed population of the RK. Similar examples in one form or another can be seen in several other countries.44

5 METHODOLOGY

Consideration of the issues of platform employment in the RK and its correlation with labour relations, particularly the imperative for Internet platform operators to conclude employment contracts with those offering their services, necessitated a reflection of the overall picture regarding platform employment subjects. In connection to this , an analysis of the statistical data provided by the Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the RK45 was carried out.

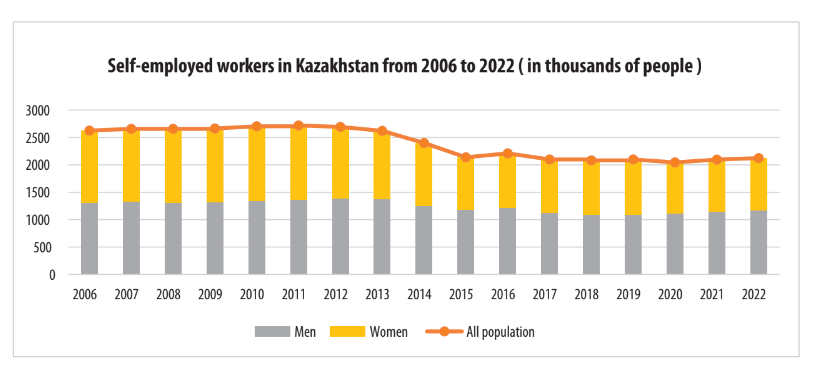

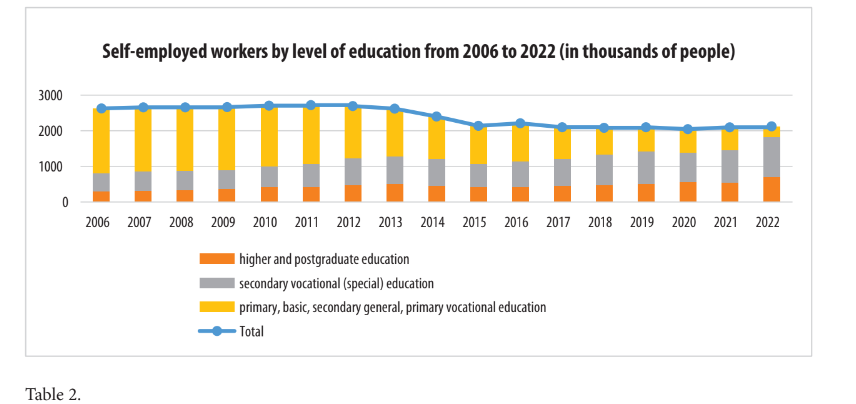

The data presented below indicate the dynamics of changes in the number of self-employed people in the RK for the period from 2006 to 2022 (Table 1). The data in Table No. 2 shows the number of self-employed, divided by the level of education in the period from 2006 to 2022 (higher and postgraduate education; technical and vocational education; primary, basic, and general secondary education).

According to Table No. 1, from 2006 to 2013, the self-employed population shows stable quantitative indicators. From 2013 to 2015, the number of self-employed workers sharply decreased from 2621 thousand people, in 2013 to 2138 thousand people in 2015. From 2015 to 2022, with some fluctuations, the number of self-employed people is kept at 2100-2000 thousand people. The ratio of self-employed men and women during the review period remains unchanged and equals proportional values. The data show that the number of self-employed people in Kazakhstan has decreased by 20% over 16 years. So, if in 2006 the share of the self- employed was 17% of the total population (15219 thousand people), then at the end of 2022, the self-employed population was 10% of the total population — 19503 thousand people.

Despite the fact that official statistics show a decrease in the number of self-employed in comparison with the total population in the RK, from the data reflected in Table No. 2, one can draw an unambiguous conclusion that the level of education among the self-employed is significantly increasing. So, if in 2006 the lion’s share of the self-employed were people with primary, basic, and general secondary education — 69% (1824 thousand people), then already in 2022 the share of people with primary, basic, general secondary education among the self-employed was 13% (297 thousand people). At the same time, the increase in self- employed people with higher education for the period from 2006 to 2022 amounted to 57%, from 297 thousand people in 2006 to 693 thousand people at the end of 2022. Notably, the number of self-employed people with technical and vocational education increased the most. Over 16 years, the number of the above self-employed has doubled (507 thousand people in 2006; 1135 thousand people in 2022).

In our opinion, the presented results of the statistical data analysis indicate the following circumstances. The growing level of education among the self-employed, which includes platform workers, confirms the likely involvement in the precariat, not only of the underclass labourers but also potentially able-bodied individuals who have not found ways and opportunities to adequately apply their abilities to work. So, graduate doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, etc., earn a living by working as a taxi or a food delivery worker. On the other hand, the level of education among the self-employed is proportional to the level of self-awareness and resistance to the manifestation of legal nihilism. It is more likely that platform employment performers, having higher or other professional education, will not only be aware of their right to decent work but will also actively defend their position 46

6 CONCLUSIONS

The lack of legal regulation of platform employment in the RK caused a number of problems, including those related to the infringement of social and labour rights of persons engaged in labour activities through Internet platforms. The Social Code of the RK, as well as other legislative initiatives, did not solve the above problems but, in our opinion, only exacerbated the existing contradictions, creating the prerequisites for the formation of a rapidly growing precariat in the RK, which, due to legislative shortcomings, may include representatives of the educated, able-bodied population. The Social Code of the RK did not allow citizens to consider themselves as a person with the right to work. As a rule, the civil law method of regulating working relations between the contractor and the operator of the Internet platform (especially the public accession agreement) is unilateral imperative. Judicial protection of labour rights seems to be ineffective since the method of civil law regulation of platform employment relations specified in the Social Code of the RK implies the full responsibility of the contractor, who voluntarily signs a public contract of the operator- Internet platform(for example, simply downloading a mobile application) refused those labour rights and guarantees that the state can and must provide to him.

In our opinion, the obligation to conclude an employment contract when hiring should also be assigned to operators of Internet platforms. However, such an approach entails the adoption of a number of significant decisions. The imposition of such a duty on the operators of Internet platforms is impossible without recognising platform employment as a type of labour relationship. The Supreme Court of the RK made similar attempts with respect to a certain Internet platform (Glovo). However, it is impossible to predict the further development and functioning of Internet platforms, in addition, there are Internet platforms that act as intermediaries in the provision of services or performance of works that cannot fall under the characteristics of the employer because they really play the role of an intermediary. We believe that the approach of the state in determining the status of the parties to platform employment, as well as the legal relations regulated between them, should be targeted and applicable to a single Internet platform or a group of Internet platforms.

Legal regulation of activities related to the use of Internet platforms, in which facts indicate the existence of ‘hidden labour relations’, must be regulated in accordance with labour legislation. At the same time, the identification of ‘hidden labour relations’ should be carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the ILO.

1Labour Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 414-V of 23 November 2015 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/ docs/K1500000414 accessed 26 August 2023.

2Shokan Alhabaev, ‘Wolt Courier Strike: Story Gets Sequel’ (Tengri News, 18 May 2021) https:// tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/zabastovka-kurerov-wolt-istoriya-poluchila-prodoljenie-437686 accessed 26 August 2023; ‘‘Four Died, 500 Were Injured’: Glovo Couriers Went on Strike in Almaty’ (Forbes, 7 July 2021) https://forbes.kz/process/chetvero_pogibli_500_postradali_kureryi_glovo_ obyyasnili_zabastovku_v_almatyi_chitat_dalee_https_rusputnikkz_society_20210707_17548457_bolee- 80-kurerov-glovo-bastuyut-v-almatyhtml accessed 26 August 2023; ‘Yandex Taxi Drivers Staged a Strike in Shymkent’ (Sputnik, 6 December 2021) https://ru.sputnik.kz/20211206/Taksisty-Yandeksa-ustroili- zabastovku-v-Shymkente-18838318.html accessed 26 August 2023; Artur Edil’geriev, ‘Yandex Taxi Drivers Staged a Strike in Petropavlovsk’ (Liter.kz, 2 February 2022) https://liter.kz/voditeli-iandeks- taksi-reshili-ustroit-zabastovku-v-petropavlovske-1643780448 accessed 26 August 2023.

3Order of the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 33 ‘On the Approval of the Rules and the Deadline for the Implementation of a Pilot Project on the Application of a Different Procedure for Tax Administration of Persons Providing Services Using Internet Platforms’ of 17 January 2023 https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/V2300031705 accessed 26 August 2023.

4Social Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 224-VII of 20 April 2023 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/ K2300000224 accessed 26 August 2023.

5Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 226-VII ‘On the Introduction of Amendments and Additions to Some Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Social Security Issues’ of 20 April 2023 https:// adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z2300000226 accessed 26 August 2023.

6International Labour Organization (ILO), Recommendation Concerning the Employment Relationship R198 of 15 June 2006 https://www.refworld.org/docid/5c77a45e7.html accessed 26 August 2023.

7Ospan A v Glovo Kazakhstan no 6001-21-00-6ap/19 (Judicial Collegium for Administrative Cases, Supreme Court of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 6 December 2021) https://office.sud.kz/courtActs/ documentList.xhtml accessed 26 August 2023.

8Social Code no 224-VII (n 4).

9Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 18-VIII ‘About Online Platforms and Online Advertising’ of 10 July 2023 https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z2300000018 accessed 26 August 2023.

10Social Code no 224-VII (n 4).

11Civil Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (General Part) no 268-XIII of 27 December 1994 https:// adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/K940001000_ accessed 26 August 2023; Civil Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Special Part) no 409 1 July 1999 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/K990000409_ accessed 26 August 2023.

12‘Platform Work’ (Eurofound, 25 November 2022) https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/ eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/platform-work accessed 26 August 2023.

13Labour Code no 414-V (n 1).

14ILO R198 (n 6).

15Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 14-VIII ‘On Professional Qualifications’ of 4 July 2023 https:// adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z2300000014 accessed 26 August 2023.

16Classifier of Professions and Specialties of Technical and Vocational, Post-Secondary Education (GK RK 05-2008) https://mcdc.kz/images/pdf/4klasifikator.pdf accessed 26 August 2023.

17Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 416-V ‘On the Civil Service of the Republic of Kazakhstan’ of 23 November 2015 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/Z1500000416 accessed 26 August 2023.

18Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 498-V ‘On Post’ of 9 April 2016 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/ Z1600000498 accessed 26 August 2023.

19Order of the Ministry of Investment and Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 349 ‘On Approval of the Rules for the Carriage of Passengers and Baggage by Road’ of 26 March 2015. https:// adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/V1500011550 accessed 26 August 2023.

20Entrepreneur Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 375-V of 29 October 2015 https://adilet.zan.kz/ eng/docs/K1500000375 accessed 26 August 2023.

21Amita Gupta v Portier Pacific Pty Ltd; Uber Australia Pty Ltd t/a Uber Eats (C2019/5651) (Fair Work Commission, 21 April 2020) https://www.fwc.gov.au/documents/decisionssigned/html/ pdf/2020fwcfb1698.pdf accessed 26 August 2023.

22Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan no 120-VI ‘On Taxes and other Obligatory Payments to the Budget (Tax Code)’ of 25 December 2017 https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/K1700000120 accessed 26 August 2023.

23Gregory Clark, ‘Factory Discipline’ (1994) 54(1) The Journal of Economic History 128, doi:10.1017/ S0022050700014029.

24Mr Michail Kaseris v Rasier Pacific VOF (U2017/9452) (Fair Work Commission, 21 December 2017) https://www.fwc.gov.au/documents/decisionssigned/html/2017fwc6610.htm accessed 26 August 2023; V Lavoro sentenza n 778/2018 (Tribunale Ordinario di Torino, 7 maggio 2018) http://www. bollettinoadapt.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/7782018.pdf accessed 26 August 2023.

25Lowman v Unemployment Compensation Board of Review 235 A.3d 278 (Pa 2020) (Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Eastern District, 24 July 2020) https://casetext.com/case/lowman-v-unemployment- comp-bd-of-review-3 accessed 26 August 2023.

26Demande de qualification de la relation de travail nr 187 — FR — 20200707 (Commission Administrative de règlement de la relation de travail (CRT), 26 octobre 2020) https://commissiearbeidsrelaties.belgium. be/docs/dossier-187-nacebel-fr.pdf accessed 26 August 2023.

27Ospan A v Glovo Kazakhstan no 6001-21-00-6ap/19 (n 7).

28ibid.

29ILO R198 (n 6).

30Ospan A v Glovo Kazakhstan no 6001-21-00-6ap/19 (n 7).

31Guy Davidov, ‘The Capability Approach and Labour Law: Identifying the Areas of Fit’ in Brian Langille (ed), The Capability Approach to Labour Law (OUP 2019) 42.

32Alan Hyde, ‘A Theory of Labour Legislation’ (1990) 38(2) Buffalo Law Review 383.

33Antonio Aloisi and Valerio De Stefano, Your Boss Is an Algorithm: Artificial Intelligence, Platform Work and Labour (Hart Pub 2022).

34Riccardo Del Punta, ‘Un diritto per il lavoro 4.0’ in Alberto Cipriani, Alessio Gramolati e Giovanni Mari (eds), Il Lavoro 4.0: La Quarta Rivoluzione industriale e le trasformazioni delle attività lavorative (Firenze UP 2018) 225-50.

35Harry W Arthurs, ‘Labour Law as the Law of Economic Subordination and Resistance: A Counterfactual?’ (2012) 10 Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy. Research Paper, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2056624.

36Brian Langille, ‘Labour Law’s Theory of Justice’ in Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds), The Idea of Labour Law (OUP 2011) 101, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199693610.003.0008.

37Alan Bogg and others (eds), The Autonomy of Labour Law (Hart Pub 2015) 316.

38Emiliana Armano, Marco Briziarelli and Elisabetta Risi (eds), Digital Platforms and Algorithmic Subjectivities (University of Westminster Press 2022) doi:10.16997/book54.

39Jan Drahokoupil and Kurt Vandaele, A Modern Guide to Labour and the Platform Economy (Elgar Modern Guides, Edward Elgar 2021) doi:10.4337/9781788975100.

40Uttam Bajwa and others, ‘The Health of Workers in the Global Gig Economy’ (2018) 14(1) Global Health 124, doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0444-8; Marie Nilsen and Trond Kongsvik, ‘Health, Safety, and Well-Being in Platform-Mediated Work: A Job Demands and Resources Perspective’ (2023) 163 Safety Science e106130, doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106130.

41Rajesh Gupta and Rajneesh Gupta, ‘Lost in the Perilous Boulevards of Gig Economy: Making of Human Drones’ (2023) 10(1) South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management 85, doi:10.1177/23220937221101259.

42Rita Remeikienė, Ligita Gasparėnienė and Romas Lazutka, ‘Working Conditions of Platform Workers in New EU Member States: Motives, Working Environment and Legal Regulations’ (2022) 15(4) Economics and Sociology 186, doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2022/15-4/9.

43Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (Bloomsbury 2011).

44Sikha Das and CS Rajeesh, ‘Urban Underclass Labourers: The Life of Delivery Workers in South India’ (2023) 58(23) Economic and Political Weekly 14; Gabriel López-Martínez, Francisco Eduardo Haz- Gomez and Salvador Manzanera-Román, ‘Identities and Precariousness in the Collabourative Economy, Neither Wage-Earner, nor Self-Employed: Emergence and Consolidation of the Homo Rider, a Case Study’ (2022) 12(1) Societies 6, doi:10.3390/soc12010006.

45Bureau of National statistics of Agency for Strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan https://stat.gov.kz/en accessed 26 August 2023.

46Dmitrij Mazorenko, ‘Couriers of all Kazakh Food Delivery Services Create a Trade Union’ (Vlast, 18 May 2021) https://vlast.kz/novosti/45043-kurery-vseh-kazahstanskih-servisov-dostavki-edy-sozdaut- profsouz.html accessed 26 August 2023; Andrey Sviridov, ‘The Couriers’ Union is Not Created at the Speed of a Courier Train’ (Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law (KIBHR), 6 October 2022) https://bureau.kz/novosti/profsoyuz-kurerov-sozdayotsya/ accessed 26 August 2023.

REFERENCES

-

Aloisi A and De Stefano V, Your Boss Is an Algorithm: Artificial Intelligence, Platform Work and Labour (Hart Pub 2022).

-

Armano E, Briziarelli M and Risi E (eds), Digital Platforms and Algorithmic Subjectivities (University of Westminster Press 2022) doi:10.16997/book54.

-

Arthurs HW, ‘Labour Law as the Law of Economic Subordination and Resistance: A Counterfactual?’ (2012) 10 Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy. Research Paper, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2056624.

-

Bajwa U and others, ‘The Health of Workers in the Global Gig Economy’ (2018) 14(1) Global Health 124, doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0444-8.

-

Bogg A and others (eds), The Autonomy of Labour Law (Hart Pub 2015).

-

Clark G, ‘Factory Discipline’ (1994) 54(1) The Journal of Economic History 128, doi:10.1017/ S0022050700014029.

-

Das S and Rajeesh CS, ‘Urban Underclass Labourers: The Life of Delivery Workers in South India’ (2023) 58(23) Economic and Political Weekly 14.

-

Davidov G, ‘The Capability Approach and Labour Law: Identifying the Areas of Fit’ in Langille B (ed), The Capability Approach to Labour Law (OUP 2019) 42.

-

Del Punta R, ‘Un diritto per il lavoro 4.0’ in Cipriani A, Gramolati A e Mari G (eds), Il Lavoro 4.0: La Quarta Rivoluzione industriale e le trasformazioni delle attività lavorative (Firenze UP 2018) 225.

-

Drahokoupil J and Vandaele K, A Modern Guide to Labour and the Platform Economy (Elgar Modern Guides, Edward Elgar 2021) doi:10.4337/9781788975100.

-

Gupta R and Gupta R, ‘Lost in the Perilous Boulevards of Gig Economy: Making of Human Drones’ (2023) 10(1) South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management 85, doi:10.1177/23220937221101259.

-

Hyde A, ‘A Theory of Labour Legislation’ (1990) 38(2) Buffalo Law Review 383.

-

Langille B, ‘Labour Law’s Theory of Justice’ in Davidov G and Langille B (eds), The Idea of Labour Law (OUP 2011) 101, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199693610.003.0008.

-

López-Martínez G, Haz-Gomez FE and Manzanera-Román S, ‘Identities and Precariousness in the Collabourative Economy, Neither Wage-Earner, nor Self-Employed: Emergence and Consolidation of the Homo Rider, a Case Study’ (2022) 12(1) Societies 6, doi:10.3390/ soc12010006.

-

Nilsen M and Kongsvik T, ‘Health, Safety, and Well-Being in Platform-Mediated Work: A Job Demands and Resources Perspective’ (2023) 163 Safety Science e106130, doi:10.1016/j. ssci.2023.106130.

-

Remeikienė R, Gasparėnienė L and Lazutka R, ‘Working Conditions of Platform Workers in New EU Member States: Motives, Working Environment and Legal Regulations’ (2022) 15(4) Economics and Sociology 186, doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2022/15-4/9.

-

Standing G, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (Bloomsbury 2011).

Authors information

Aigerim Zhumabayeva

* Master of Laws, PhD Candidate, Eurasian National University named after L.N. Gumilyov, Specialist of PVC RSE ‘Institute of Parliamentarism’ of the Logistics Directorate, Kazakhstan, Astana zhumabayeva@umto.kz https://orcid. org/0000-0003-3376-4325

Corresponding author, responsible for writing and research.

Amanzhol Nurmagambetov

** Dr. Sc. (Law), Professor, Head of the Department of Civil, Labour and Environmental Law of the Faculty of Law, Eurasian National University named after L.N. Gumilyov, Kazakhstan vest_law@enu.kz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9026-9019 Author’s institutional email

Co-author, responsible for writing — review&editing and methodology.

Competing interests: Any competing interests were included by authors.

Disclaimer: The authors declare that their opinions and views expressed in this manuscript are free of any impact of any organizations.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Translation: The content of this article was translated with the participation of third parties under the authors’ responsibility.

About this article

Cite this article A Zhumabayeva, A Nurmagambetov ‘Platform employment and the obligation to conclude an employment contract in the Republic of Kazakhstan: issues of theory and practice’ (2023) 4 (21) Access to Justice in Eastern Europe. https://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18-6.4-a000411

Submitted on 13 Mar 2023 / Revised 26 Aug 2023 / Approved 11 Sep 2023

Published ONLINE: 20 Oct 2023

DOI https://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18-6.4-a000411

Managing editor — Mag. Polina Siadova. English Editor — Julie Bold.

Summary: 1. Introduction. — 2. Literature review. — 3. Methodology. — 4. Data. — 5. Results. – 6. Limitations of the study. — 7. Conclusions. — 8. Discussion & Legal aspects.

Keywords: Shadow Economy, Economic Growth, Panel Regression Model, Tax Revenue, Effective Tax Rate, Baltic States

Rights and Permissions

Copyright:© 2023 Zhumabayeva Aigerim and Nurmagambetov Amanzhol. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.