Summary: 1. Introduction. – 2. Literature Review. – 2.1. Social Factors. – 2.2. Economic Factors. – 2.3. Political Factors. – 2.4. Legal Factors. – 3. Methods. – 4. Results: Modelling and Forecasting. – 5. Conclusion.

ABSTRACT

Background:Migration processes play an important role in the economic development of a country and form the human resources necessary for developing countries. Therefore, forming a favourable legislative framework for a certain category of migrants affects the attraction of the necessary human resources for the country.

Motivation:Generally, the level of immigration has risen over the last 50 years, and around 3.6% of the total population in the world are immigrants. Identifying the influencing factors that motivate people to migrate is very important. This understanding informs well-designed immigration and effective solutions for foreign policy.

Aim:To analyse and model the impact of the factors influencing the choice of the destination country, examining what attracts a person to a country or, on the contrary, why a country may not be chosen. Additionally, this paper seeks to forecast the dynamics of immigration in Spain for 2022-2024 under the impact of selected factors for analysis

Methods:To create a regression model using the R-Studio software based on a data set for the 2000-2021 years. The scientific hypothesis is that the following could have an influence on the level of immigration to Spain: inflation, level of employment and education, government spending on social protection, the share of the ICT sector in the GDP of the country, as well as the economic crisis in the USA for 2007, and legal factor such as the presence of open borders for the African population in 2019, a characteristic not shared by other European countries. The last two indicators, proven significant in attracting immigrants, were incorporated into the model as dummy variables.

Results and Conclusions:The research proved a non-linear negative impact of a logarithm of spending on social protection expenditure and the third degree of inflation—conversely, a positive impact of the third degree of employment level. Additionally, the forecast of immigration in Spain under the impact of the above factors was discussed. The paper will be of interest to the government since migration is not only important in terms of the country's demographic structure but also has a direct impact on a country’s national economy. It can either strengthen or weaken the country’s economic development, making it significant to policymakers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today, migration processes are one of the biggest problems of the 21st century. Almost every modern person has experienced a situation where their relatives or close friends migrated abroad. While migration processes have persisted to this day, the increasing economic instability and tension in various countries' social and political situations have only intensified and accelerated migration processes. More and more often, people began to leave the Motherland not because of poverty but because of the hope of finding a safe place to live.

The concept of immigration, from the viewpoint of the country of arrival, reflects the act of moving to a country that is not the country of habitual residence or nationality. Therefore, the country of destination effectively becomes their new country of habitual residence.

Overall, the number of immigrants has grown over the past 50 years. Current global estimates put the total number of people living in another country than their birth country in 2020 at 281 million, 128 million more than in 1990 and more than three times the estimated number in 1970. That is, about 3.6% of the general population in the world are immigrants.1

This research considers the current situation of immigration to Spain, what factors influence it, and what measures can be taken to at least partially control it. Additionally, the prediction of immigration in Spain considers the influence of the factors present.

Such research should be of particular interest to the governments of different countries from an economic point of view because immigration processes significantly influence the demographic structure of the country’s population. Moreover, they strongly influence the economic development of the country, which in turn can strengthen or, on the contrary, weaken the national economy.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Numerous scientific studies conducted by researchers from different countries on migration processes analyse the influence of social, political and economic factors on immigration processes.

2.1. Social Factors

In the context of immigration from North America to Israel, Israeli researchers confirm that social networks can increase a desire to immigrate.2 This relationship mirrors the findings in a study by Facchini et al.3 conducted in Japan. Additionally, Fischer’s4 work explains the importance of language skills when considering relationships between house prices and immigrant in-flows. The author highlights that non-common-language immigrants value amenities more than those from common-language countries, which are sensitive to house prices.

In an article by Segal et al.,5 education and social opportunities and the presence of international connections incentivise immigration. The authors highlight that the host country may invite immigrants to serve in labour markets, making it more engaging for them. Also, the impact of education on the immigration process as a significant factor is revealed in many other works.6

In the study by Young et al.,7 a multi-level analysis with mixed effects multinomial logistic regression models is presented to investigate the impact on immigration policy. The results show that the macro-level economic situation does not exhibit a significant association with immigration policy, while the socio-cultural situation detects unexpected conclusions. As for the national security domain, terrorist acts show a connection with anti-immigration policy.

González and Ortega’s8 study asserts that immigrants' location choices are significantly driven by early migrant settlements. The results of another paper by Ashby et al.9 confirm that immigrants tend towards states with higher numbers of immigrants of the same nationality, shorter distances, higher salaries, and smaller populations.

2.2. Economic Factors

Hu et al.10 explored whether immigration decision-making is associated with the quality of urban air in the case of China. Researchers confirmed that among determinants of immigration, air quality was worse than GDP, salaries, industrial structures and public services.

A study by Lewer and Van den Berg11 offers a regression model based on the gravity model of international trade to test the influence on immigration, showing that the attractive force between the country of immigrant’s birth and destination countries depends on the difference between wages in the two countries. Another study considering immigrants to the United States uses a Tobit technique to estimate a strong correlation between immigrant flow and welfare generosity.12

In Boubtane et al.’s paper13, using the panel Granger approach for causality testing of Kònya for 22 OECD countries, the authors prove that unemployment only in Portugal negatively causes immigration. Also, in four countries, economic growth positively causes immigration. Moreover, Carella, Gurrieri and Lorizio14 corroborate these results, affirming that in Italy and Spain, immigrants' continuous and rapid growth is paralleled by a corresponding increase in non-profit organisations.

The research by Grau Grau and Ramirez Lopez15 describes immigration and factors during the business cycle.16 The results show the factors related to GDP and public debt significantly justify the immigration level since the start of the crisis, while the expectancy of life duration and pollution level are determining factors in all phases. Also, the paper by Rodenas et al. presents that after six years of economic recession in Spain, there has been no complete halt in the entrance of immigrants or a mass outflow of ones.

Sekiguchi et al.’s17 paper on the connections between people's motivations to migrate to their hometowns and their evaluations of the living environments of their country and current residence using an analysis with a decision tree for the case of Japan is valuable. The critical factor for reducing U-turn motivation researchers highlight convenience-related living conditions.

The research results of Oigenblick and Kirschenbaum18 suggest that the probability of making an immigration decision depends on the presence of well-established and supportive relatives at the destination and intentions to own property and engage in economic activities.

2.3. Political Factors

Godenau19 proves changes in border management introduced by Spain and the EU decreased the influx of irregular immigrants.

Another study by Klimaviciute et al.20 considers the effect of policy and the Brexit referendum 2016 on the immigration decisions of young Lithuanian and Polish migrants. The results show that the referendum had a small impact on the immigrant's decisions, giving way, instead, to work, family, and lifestyle considerations.

The opposite opinion is presented in the article by Mendoza,21 where the state's action is a major element in considering immigration. The significant role of political institutions in considering the influx of immigrants is described in other studies.22

From the resources discussed above, it can be seen that the policies and actions of the chosen state play a crucial role in considering the country's attractiveness to foreign immigrants. As for Spain, despite being a country with a significant number of emigrants for quite a long time, the government still found methods not only to reduce the outflow of people from the country but also managed to attract a fairly large number of foreign migrants, that made it one of the leaders' positions among European countries. The study of factors influencing immigration is a significant issue, both from the viewpoint of demographic and migration policy and from the economic point of view. After all, the increase in the share of migrants creates additional demand for consumer goods and other products and services on the market that contribute to the creation of GDP and labour supply. Highly skilled labour resources have scientific and technical potential, accelerating the country's economic growth. So, this study should be of particular interest to the government.

2.4. Legal Factors

At the time of the creation of the European Union (EU), common policies were introduced, including migration legislation, which contains a critical concept of politics, which caused tensions among EU member states that continue to this day. The member states of the Schengen Agreement agreed to a common visa system, free movement of workers within the borders of the Schengen zone countries, and mutual exchange of information on border security.23 Although this agreement provides the genesis policy on the free movement of people across borders within the Schengen area, it does not define the contours of migration policy, which later became a controversial feature of EU migration policy and a major obstacle in the way to establishing a reliable migration policy in the EU.

Following the Maastricht Treaty, the Amsterdam Treaty 1997 was influential in shaping migrant policy.24 According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, the Treaty of Amsterdam was vital because it built protocols and standard procedures for immigrants and asylum seekers, protecting the rights of people from third-world countries. In general, the Treaty of Amsterdam was the first clear and visible attempt to formalise EU migration policy and procedures, depriving EU member states of their autonomy in certain aspects of immigration.

The Hague Program was introduced in 2004, which defined human rights and the rights of asylum seekers and immigrants.25 The last significant event in EU legislation, particularly regarding EU migration policy, was the Dublin Convention in 1990, revised in 2013.26 This convention is considered the most controversial and notorious EU response policy to the migration problem and has a significant framework in the EU migration crisis. This policy has created a severe problem for the EU, especially in the countries of entry, carrying a disproportionate burden on Southern Europe, which was already struggling with a huge influx of immigrants and asylum seekers. Controversial migration policies under the Dublin Convention have led to resource shortages, humanitarian problems, and inadequate refugee centres in southern Europe, including Italy, Greece, and Spain.

Considerable attention is paid to the legal regulation of the fight against illegal migration in the EU. The system of legal acts of the EU in the field of combating illegal migration is quite extensive. Strict restriction of legal methods of entry and the employment of migrants leads to an increase in illegal migrants, which, in turn, initiates the strengthening of legislation in the field of combating illegal migration.

Regulation 539/2001 dated March 15 2001 ‘On establishing a list of third countries whose citizens must have a visa and countries whose citizens are exempt from visas’ regulates the conditions of entry of foreigners into the EU.27 In fact, this document started the socalled "black" and "white" lists of third countries, which allowed the European Union to curb illegal migration, but not prevent it in full. Directive 2009/50/EU dated May 25 2009, ‘On establishing the conditions of entry and stay of citizens of third countries for work’ formulates attractive conditions for the legal entry and stay in EU countries of highly qualified specialists from third countries.28 Compared to other legal immigrants in the EU, a simplified procedure for exercising some rights is provided for such specialists. It should be noted here that measures such as granting the most favourable migration regime to migrants who are highly qualified specialists have not been able to significantly reduce illegal migration because, for low-skilled specialists, the migration regime remained the same.

The importance of adopting a global approach to the migration process while making the best use of legal migration, ensuring the protection of those in need, combating irregular migration, and effectively protecting borders must be emphasised.

The research questions are:

- What socio-economic factors influence the decision of foreign migrants to choose Spain as their permanent residence?

- What is the projected number of immigrants to Spain, taking into account the influence of the considered factors?

3 METHODS

Modelling the influence of the socio-economic factors on immigration to Spain was done by building regression models. We used the ordinary least squares (OLS) method to investigate the relationship between the selected factors and the modelled variable. Then, we checked the model for adequacy, significance of factors, autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and multicollinearity, normality of residuals, stability and correctness of functional form. Finally, using a relevant model, we predicted future situations in Spain.

The analysed period is from 2000 to 2021 inclusive. The values of all variables were taken from databases of the EU Statistical Office (Eurostat)29 and the World Bank.30 Regression models were built using R-Studio software.

However, before directly reviewing the model, we analysed the indicators selected for the study.

Among a large number of possible influencing factors, the following were chosen for consideration: government spending on social protection, employment of the population, inflation, the level of education, the share of the ICT (information and communications technology) sector in the country's GDP, as well as two more factors that attracted a large number of immigrants, one of which is the economic crisis in the USA for 2007, and another is the legal factor such as the presence of open borders for the African population in 2019, which other European countries don’t have. Factors were selected according to the level of correlation with the dependent variable and their significance in the model chosen. In addition, the choice was also influenced by our assumptions based on the research of other scientists. In the first stage, we consider each of them in more detail to analyse their dynamics in the selected period.

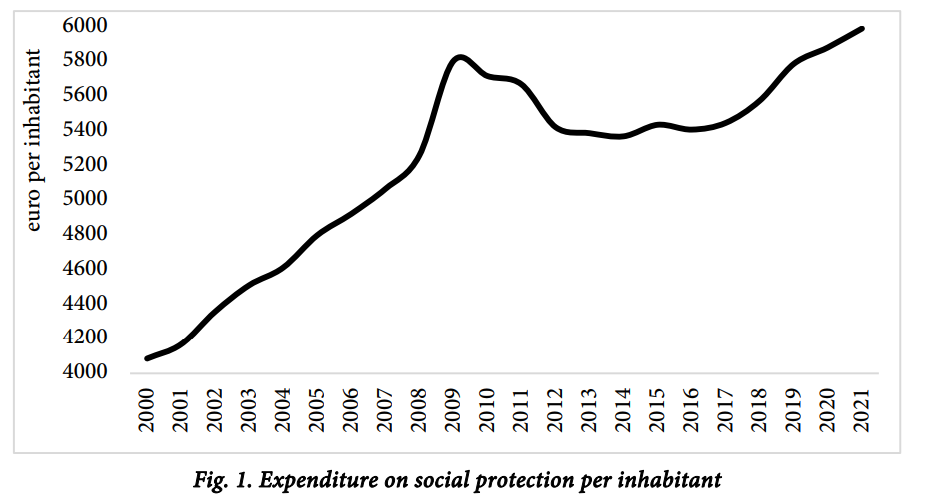

First is social protection spending, which reflects an overall measure of the expenditure on nationals and immigrants. The selected data are aggregated, including social benefits and administrative costs.

Access to social security programs that are part of the social security system is mainly based on periodic contributions. Health care, education, personal social services and social assistance operate according to the residence criterion (any person registered as a resident of Spain).

However, one drawback is the important role of the shadow economy in Spain's production system, which prevents workers from accessing the protection of contributory social security schemes. Besides, the economic crisis that began in 2008 led to a considerable reduction in social spending in Spain, including immigrants.31 Regarding the dynamics of the indicator during the analysed period, it had a positive trend, growing moderately (Fig. 1).

Source: authors’ calculations based on Eurostat (2023)

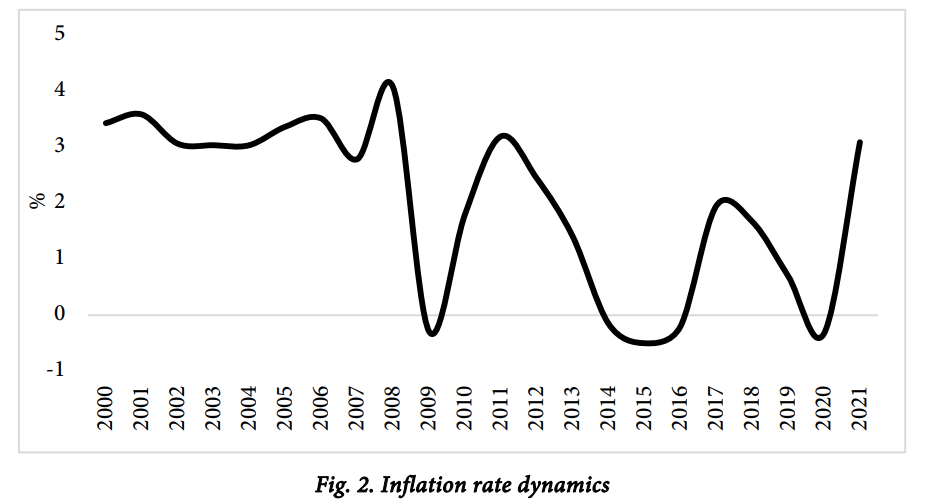

The next factor is inflation (Fig. 2). The level of consumer price inflation in Spain over the past 61 years has ranged from -0.5% to 24.5%. The subsequent nature of the inflation rate describes a change of about 2-3% every 2-3 years. The inflation rate for 2021 is calculated to be 3.2%.32

Source: authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2023)

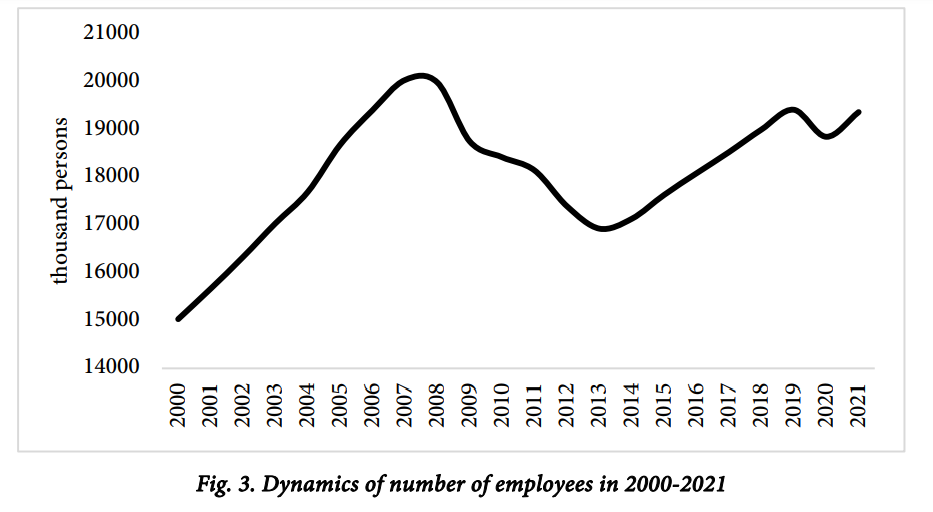

Regarding employment, an indicator was chosen that reflects the number of the working population of Spain aged 20-64. A significant growing share of the employed population may indicate a demand for labour, which in most cases is the primary goal of foreign immigrants. However, it should be noted that despite improvements in the Spanish labour market, it still has serious structural problems such as susceptibility to changes, high unemployment rates, seasonality, a low level of workers skills, and a large number of discouraged young people who are neither employed nor in education.33 During the analysed period, employed persons grew moderately, ranging from 15,000 to 20,000 (Fig. 3).

Source: authors’ calculations based on Eurostat (2023)

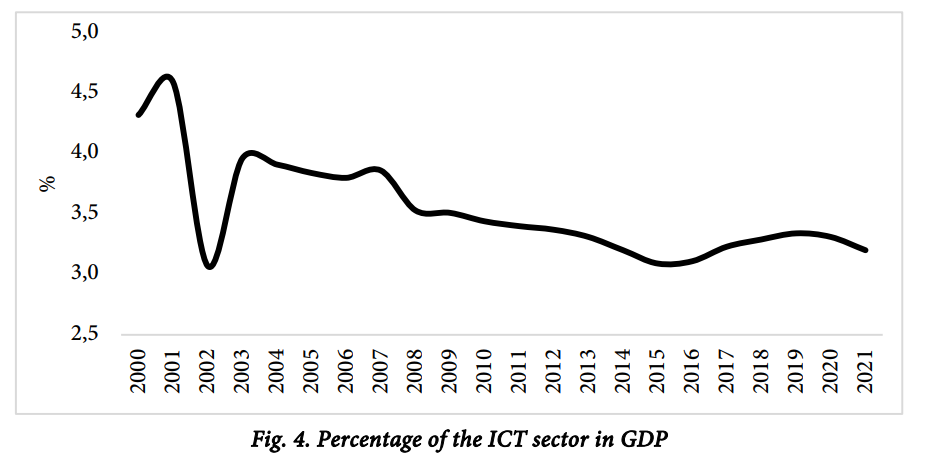

Today, the development of digital culture and digitalisation, in general, are quite important for the country because, with the help of digital technologies, a modern person interacts with the environment, business, and even the government. Therefore, the share of the ICT sector in Spain's GDP, in this case, acts as a kind of assessment of the country's digitisation state and is explicitly directed at the study of the impact on immigration and whether this factor will attract foreign migrants. In general, the volume of income from this sector for ten years is almost stable (Fig. 4), which may indicate either the lack of development of this industry or the lack of suitably qualified personnel, which immigrants can become.

Source: authors’ calculations based on Eurostat (2023)

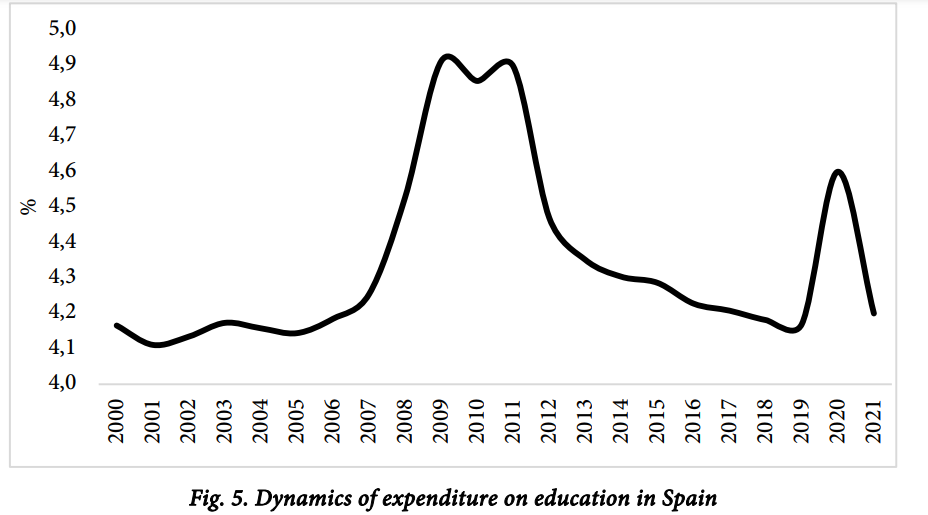

In addition to the indicators discussed above, education is a somewhat important factor for an immigrant, whether a student or a young family, when choosing a country. So, to take this factor into account, the share of education expenses that the government allocates from GDP was selected because it is from the latter that the financing of most educational projects that will contribute to the general development of education and qualifications of future employees depends. In general, the share of costs varies between 4-5% (Fig. 5). During 2007-2009, there was a rather significant increase in expenses for the analysed period, but the dynamics of 2011-2017 reflect a sharp return to the level of expenses identical to 2007.

Source: authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2023)

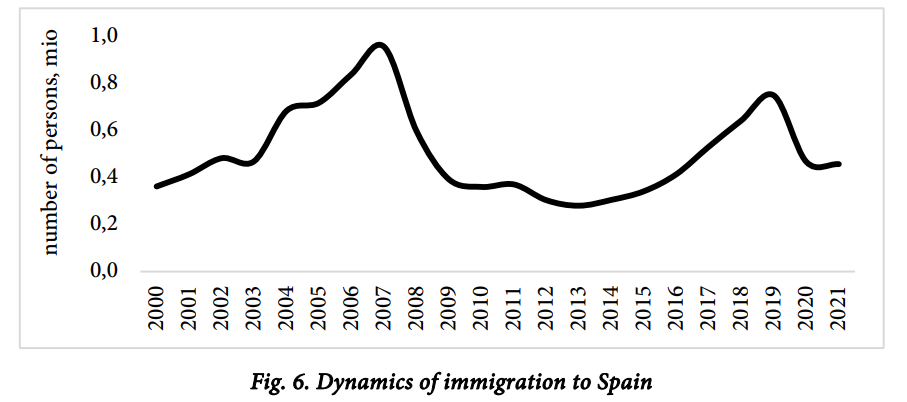

Two factors were also taken into account, which influenced a fairly significant increase in the number of immigrants in 2007 and 2019 (Fig. 6). In 2007, this is the beginning of the economic crisis in the United States,34 and accordingly, in 2019, the main factor was the presence of open borders for the African population, which did not provide other European countries.35

The 2019 Africa Plan has three aspects which have legal confirmation. Firstly, it strives to go beyond perceptions of Africa as merely a passive recipient of humanitarian assistance towards treating the continent as an economic partner through strengthened trade and investment. Secondly, the plan espouses job creation for migrants in economic hubs in South Africa, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. It recognises that migration governance cannot be successful without taking into account broader governance issues, security, and economic growth. The plan strives to integrate trade, development, and security objectives. Thirdly, the plan pursues a comprehensive approach. It declares that it will look beyond migration control to embrace issues such as peace and security, political stability, economic growth, and sustainable development. The plan strives to offer more than a Eurocentric lens, recognising the importance of intra-regional mobility in Africa and that only a minority of migrants (around 15 percent) from sub-Saharan Africa travel to Europe.

Enabling greater migration within regions and between regions such as West Africa and Europe would be of great benefit in allowing people to travel legally and safely and in showing the public that governments can have in place planned migration governance structures that are both humane and address the public’s invasion anxiety. Both Spain and the EU can go further on this.36

Source: authors’ calculations based on Eurostat (2023)

We note the designations of variables used in the model:

― Immigrant – number of immigrants, simulated indicator;

Factors:

- Social protect – expenses for social protection of the population;

- Inflation – inflation level;

- Employment – the number of employed persons aged 20-64;

- ICT – the share of the ICT sector in GDP;

- Education – share of education expenses in GDP;

- A – dummy variable, the beginning of an economic crisis outside the country;

- B – dummy variable, the presence of open borders.

So, for now, we have considered the characteristics of all possible factors that will be used in constructing the regression model. The conclusion is that these indicators describe a certain socio-economic attractiveness and affect the development of the country's economy.

4 RESULTS: MODELLING AND FORECASTING

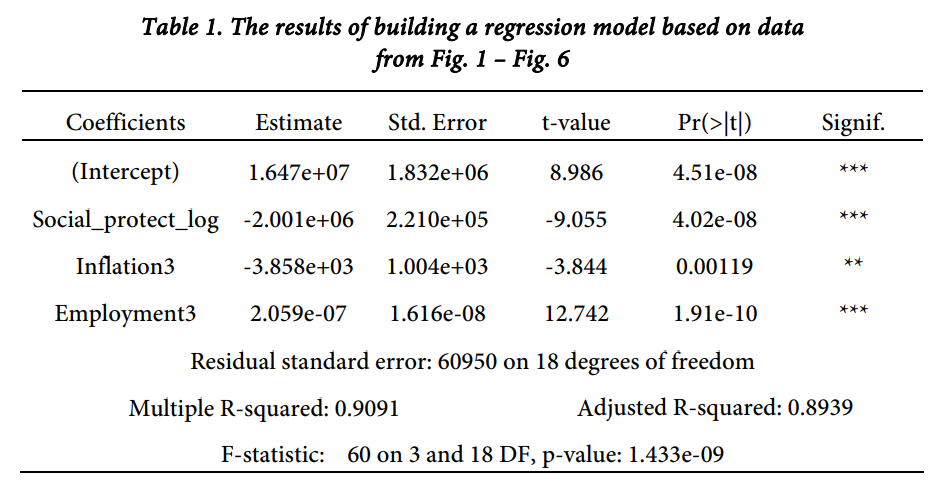

After constructing various models, a trend was observed that with the growth of the degree of the employment rate, the quality of the model improved. Using this principle, a model was built that included the logarithmic values of the factor corresponding to the costs of social protection, the level of inflation, and employment in the third degree. Such a functional form of the model equation is the most relevant, considering the adjusted R2 and model validation using the RESET test, which shows the correctness of non-linear transformation. As we can see, this model does not include factors such as the ICT sector's share in GDP, spending on education, the beginning of the economic crisis, and the openness of borders. However, with a probability of 95%, the model is adequate since the p-value = 1.433e-09, which is less than 0.05, and all coefficients are significant. The quality is high since about 90.91% is described by the factors used, and only 9.09% is due to other unexamined factors (Table 1). According to Chow's criterion, we have a stable model according to both the dispersion and modification criteria. According to Jarque-Bera’s criterion, the residuals have a normal distribution, so the constructed model has high quality and can be implemented for future analysis and forecasting.

The presented regression equation describes how the number of immigrants will change under the existing relevant situation in the country, which factors improve the attractiveness of Spain for foreign migrants, and which, on the contrary, will leave it off the list of choices. To reflect the quantitative impact, elasticity coefficients were calculated for each factor.

Source: authors’ calculations in R-Studio based on the collected dataset

The regression equation has the following form:

????????? = 1.647? + 07 − 2.001? + 06 ∗ ??????௧௧ౢౝ షయ.ఴఱఴ + 03 ∗ ∗ ?????????3 + 2.059? − 07 ∗ ??????????3 + ?

Thus, increasing government social spending per person by 1% reduces the number of foreign migrants by 33.75%. Traditionally, the increase in social expenditure positively impacts the rise in the number of migrants. The strength of the impact may vary, but in such conditions, the reason for such a large negative impact may be that the majority of expenditures are for the payment of the social needs of the country's citizens. In contrast, expenditures for assistance to immigrants are small, increasing the competition between immigrants for social support from the government and making the procedure more complicated. Also, as discussed above, there are several reasons why immigrants are unable to receive a given number of payments, which in turn may not affect their behaviour or, on the contrary, make Spain less attractive as a possible residence.

An increase in the inflation rate by 1% provokes a decrease in immigration by 0.15%; a decline, on the contrary, stimulates their inflow by 0.15%. But, probably, one of the most important factors in choosing a country for changing the place of permanent residence is the possibility of employment. Thus, according to the obtained model, an increase in the number of employed persons, which reflects an increase in the demand for labour by 1%, increases the number of immigrants by 2.43%; that is, it stimulates foreign immigrants to decide to migrate specifically to Spain.

Having checked our model for adequacy, quality, stability, normality of residuals’ distribution, etc., one should not forget important problems that may appear in the analysis of any regression model, such as multicollinearity, heteroskedasticity, and autocorrelation.

Thus, according to the Farr-Glauber statistical criterion, the analysed regression model has multicollinearity.

A critical issue is also checking the model for heteroskedasticity, violating the second condition regarding model disturbances, namely equality of variances. There are several criteria for its detection. Thus, the following criteria of Goldfeld–Quandt, Glaser, and White were considered in this study.

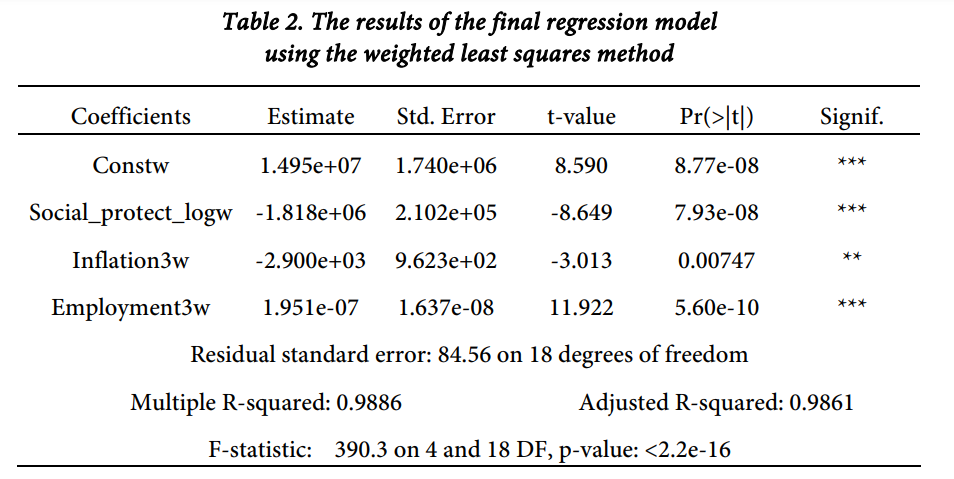

Almost all the considered criteria confirm the presence of heteroskedasticity in the analysed model, which is not good enough. After all, in this case, the method of least squares estimation is not effective; that is, they need to have the smallest variance, which leads to incorrect hypothesis testing. However, some methods will help to eliminate it; in this work, the weighted least squares method, according to White, was used (table 2).

Source: authors’ calculations in R-Studio based on the collected dataset

Analysing the obtained model, it should be noted that it is adequate (p-value: < 2.2e-16, which is less than 0.05), describes the modelled dependence quite well, as the coefficient of determination is greater than 0.9 (R2 = 0.9886), and all variables are significant.

For now, it remains to test our model for autocorrelation of the residuals, which is also a rather important issue. After all, in her case, least squares assessments will not be effective, and the results of testing hypotheses and forecasts will be incorrect. There are also some criteria for its verification. Thus, the Breusch-Godfrey, Cochrane-Orcutt, and DurbinWatson criteria were considered and also verified by constructing auxiliary models with lags. Most methods confirmed the fact of the absence of autocorrelation. That is, this model is suitable for practical use.

The final regression equation has the following form:

????????? = 1.495? + 07 − 1.818? + 06 ∗ ??????௧௧ೢ − 2.900? + +03 ∗ ?????????3 + 1.951? − 07 ∗ ??????????3 + �

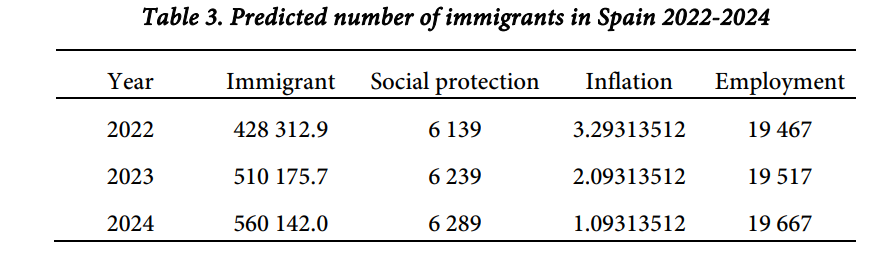

Currently, it is possible to apply the model in practice and try to predict the situation during the years 2022-2024 regarding the number of immigrants in Spain on imaginary data (table 3). The source of the data of factors is our assumptions based on the current trend of each independent variable.

Source: authors’ calculations in R-Studio based on the collected dataset

How can we observe the modelled relationship between the dependent variable and the regressors that actually exist? Thus, the increase in the number of employed people did not contribute to the rise in the number of immigrants to Spain in 2022 compared to 2021 since there is also an increase in government spending on social protection and the inflation rate, which harm the change in the number of immigrants, and, as discussed above, it is social benefits that have the greatest impact. With a decrease in inflation in 2023 by one percentage point, there was an increase in the number of immigrants compared to 2022 due to an increase in the number of employed people and government spending. However, the largest increase in the number of immigrants can be achieved by reducing government spending and the level of inflation while increasing the demand for labour, which is reflected in the data for 2024.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this work, the issue of immigration was raised, namely, the possible factors affecting the choice of country, which every immigrant faces. Thus, the largest number of foreign immigrants is concentrated in Europe, among which Germany, Great Britain, Spain, Italy, and France stand out in great demand. The third most popular country - Spain - was chosen for consideration.

The following indicators were selected and characterised: social protection expenditures, inflation rate, number of employed persons, the percentage of the ICT sector in GDP, and education expenditures. It should also be noted that in the general examination of the situation that has developed in Spain over the past 20 years, two more dummy variables were identified and introduced to the model, namely the presence or onset of an economic crisis and open borders, which caused the largest influx of immigrants in 2007 and 2019. But, in the constructed model, these dummy variables were insignificant, indicating that their impact is not so important.

A number of both linear and non-linear models have been constructed to identify existing relationships between the number of immigrants to Spain and certain socio-economic factors. It should be noted that not all of the above factors were included in the model, including the percentage of the ICT sector in Spain's GDP, spending on education, the onset of the economic crisis, and open borders. In this case, the investigated dependence was best described by a model whose modelling variable depended on certain non-linear factors (logarithmic social protection costs, inflation rate, and the number of employed persons in the third degree). This model describes 90.91% of the studied dependence under the influence of the selected factors, and only 9.09% is due to other unconsidered factors, which is quite good. The biggest impact on the number of immigrants in Spain, and a negative one, is government spending on social protection: a 1% increase in expenditures causes a 32.44% decrease in the number of immigrants. This may be because a relatively significant share of the costs, after all, falls on Spanish citizens, as well as the fact of the complex mechanism of obtaining them. As for the inflation rate, it also has a negative effect on the modelling variable, but it is rather insignificant. Thus, when the inflation rate increases by 1%, the inflow of foreign migrants decreases by 0.12%. Only the number of employed persons characterises a positive trend towards the growth of immigrants. Their increase of 1% will attract 2.38% more immigrants. It should also be noted that autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity are absent in this model; the model is stable and adequate, all factors are significant, and residuals have a normal distribution, but multicollinearity is present, which should be kept in mind. In addition, a forecast for 2022-2024 was built, reflecting this model's operation and logic.

So, migration processes, in turn, immigration, are quite important topics when considering the country's economy because they also directly affect economic processes, which, as a result, can be accompanied by strengthening or, on the contrary, weakening of the country's economic growth. Therefore, the construction and use of such econometric models can not only predict the future situation but also help to find certain factors with the help of which certain phenomena and processes can be regulated.

The research findings hold economic significance for governments across diverse countries. Immigration processes play a crucial role in shaping the demographic structure of the country’s population, strongly influencing its economic development. This, in turn, can either strengthen or, on the contrary, weaken the national economy.

But also, it is important to not forget that immigration and the influencing factors may vary across different countries. This variation warrants future consideration and presents an avenue for future research. Additionally, as a direction of future research, it is relevant to mention checking the influence of other factors, predicting immigration from other European countries and comparing the dynamics involved in these scenarios.

1‘About Migration’ (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2023)

2Karin Amit and Ilan Riss, ‘The Role Of Social Networks in the Immigration Decision-Making Process: The Case of North American Immigration to Israel’ (2007) 25(3) Immigrants & Minorities 290, doi:10.1080/02619280802407517.

3Giovanni Facchini, Yotam Margalit and Hiroyuki Nakata, ‘Countering Public Opposition to Immigration: The Impact of Information Campaigns’ (2022) 141(C) European Economic Review 103959, doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103959.

4Andreas M Fischer, ‘Immigrant Language Barriers and House Prices’ (2012) 42(3) Regional Science and Urban Economics 389, doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.11.003.

5Uma A Segal, Nazneen S Mayadas and Doreen Elliott, ‘A Framework for Immigration’ (2006) 4(1) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 3, doi:10.1300/J500v04n01_02.

6Joaquín Naval, ‘Wealth Constraints, Migrant Selection, and Inequality in Developing Countries’ (2019) 23(2) Macroeconomics Dynamics 535, doi:10.1017/S1365100516001255; Andreea Simona Săseanu and Raluca Mariana Petrescu, ‘Education and Migration. The Case of Romanian Immigrants in Andalusia, Spain’ (2012) 46 Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 4077, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.201

7Yvette Young, Peter Loebach and Kim Korinek, ‘Building Walls or opening Borders? Global Immigration Policy Attitudes Across Economic, Cultural and Human Security Contexts’ (2018) 75 Social Science Research 83, doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.006.

8Libertad González and Francesc Ortega, ‘How do Very Open Economies Adjust to Large Immigration Flows? Evidence from Spanish Regions’ (2011) 18(1) Labour Economics 57, doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2010.06.001.

9Nathan J Ashby, Avilia Bueno and Deborah Martínez Villarreal, ‘The Determinants of Immigration from Mexico to the United States: A State-to-State Analysis’ (2013) 20(7) Applied Economics Letters 638, doi:10.1080/13504851.2012.727964.

10Zhigao Hu and others, ‘Longing for the Blue Sky: Urban Air Quality and the Individual Decision to Immigrate’ (2022) 79 Journal of Asian Economics 101437, doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101437.

11Joshua J Lewer and Hendrik Van den Berg, ‘A Gravity Model of Immigration’ (2008) 99(1) Economics Letters 164, doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2007.06.019.

12Marvin E Dodson (III), ‘Welfare Generosity and Location Choices Among New United States Immigrants’ (2001) 21(1) International Review of Law and Economics 47, doi:10.1016/S0144- 8188(00)00040-5.

13Ekrame Boubtane, Dramane Coulibaly and Christophe Rault, ‘Immigration, Unemployment and GDP in the Host Country: Bootstrap Panel Granger Causality Analysis on OECD Countries’ (2013) 33(C) Economic Modelling 261, doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.04.017.

14Maria Carella, Antonia Rosa Gurrieri and Marilene Lorizio, ‘The Role of Non-Profit Organisations in Migration Policies: Spain and Italy Compared’ (2007) 36(6) The Journal of Socio-Economics 914, doi:10.1016/j.socec.2007.08.001.

15Carmen Ródenas, Mónica Martí and Ángel León, ‘A New Pattern in International Mobility? The Case of Spain in the Great Crisis’ (2017) 76(299) Investigación económica 153, doi:10.1016/j.inveco.2017.02.003.

16Alfredo Juan Grau Grau and Federico Ramírez López, ‘Determinants of Immigration in Europe. The Relevance of Life Expectancy and Environmental Sustainability’ (2017) 9(7) Sustainability 1093, doi:10.3390/su9071093.

17Tatsuya Sekiguchi and others, ‘The Effects of Differences in Individual Characteristics And Regional Living Environments on the Motivation to Immigrate to Hometowns: A Decision Tree Analysis’ (2019) 9(3) Applied Sciences-Basel 2748, doi:10.3390/app9132748.

18Ludmilla Oigenblick and Alan Kirschenbaum, ‘Tourism and Immigration: Com-Paring Alternative Approaches’ (2002) 29(4) Annals of Tourism Research 1086, doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00023-3.

19Dirk Godenau, ‘Irregular Maritime Immigration in the Canary Islands: Externalization and Communautarisation in the Social Construction of Borders’ (2014) 12(2) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 123, doi:10.1080/15562948.2014.893384.

20Luka Klimaviciute and others, ‘The Impact of Brexit on Young Poles and Lithuanians in the UK: Reinforced Temporariness of Migration Decisions’ (2020) 9(1) Central and Eastern European Migration Review 127, doi:10.17467/ceemr.2020.06.

21Cristóbal Mendoza, ‘The Role of the State in Influencing African Labour Outcomes in Spain and Portugal’ (2001) 32(2) Geoforum 167, doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00053-6.

22Nusrate Aziz, Murshed Chowdhury and Arusha Cooray, ‘Why do People from Wealthy Countries Migrate?’ (2022) 73(C) European Journal of Political Economy 102, doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102156; Deborah A Cobb-Clark, ‘Incorporating US Policy into a Model of the Immigration Decision’ (1998) 20(5) Journal of Policy Modelling 621, doi:10.1016/S0161- 8938(97)00064-1; Henrik Emilsson, ‘Who Gets in and Why? The Swedish Experience with DemandDriven Labour Migration - Some Preliminary Results’ (2014) 4(3) Nordic Journal of Migration Research 134, doi:10.2478/njmr-2014-0017; Ricard Zapata-Barrero, ‘Perceptions and Realities of Moroccan Immigration Flows and Spanish Policies’ (2008) 6(3) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 382, doi:10.1080/15362940802371697.

23‘Schengen Area’ (European Commission, 2023)

24Treaty of Amsterdam amending the Treaty on European Union, the Treaties establishing the

European Communities and certain related acts (signed on 2 October 1997) [1997] OJ C 340

25The Hague Programme: strengthening freedom, security and justice in the European Union (adopted

of November 2004) [2005] OJ C 53

26Convention determining the State responsible for examining applications for asylum lodged in one

of the Member States of the European Communities - Dublin Convention (signed on 15 June 1990)

[1997] OJ C 254

27Council Regulation (EC) 539/2001 of 15 March 2001 ‘Listing the third countries whose nationals must

be in possession of visas when crossing the external borders and those whose nationals are exempt

from that requirement’ [2001] OJ L 81

28Council Directive 2009/50/EC of 25 May 2009 ‘On the conditions of entry and residence of thirdcountry nationals for the purposes of highly qualified employment’ [2009] OJ L 155

29Eurostat

30World Bank

31Francisco Javier Moreno-Fuentes, ‘Migrants’ Access to Social Protection in Spain’ in JM Lafleur and D Vintila (eds), Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond vol 1 (Springer Cham 2020) 405, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-51241-5_27.

32‘Inflation Rates in Spain’ (World Data, 2023)

33‘Work in Spain’ (SEPE, 2023)

34Vilmantė Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė and others, Migration Culture: A Comparative Perspective (Springer Cham 2021) doi:10.1007/978-3-030-73014-7.

35Victoria Carty, The Immigration Crisis in Europe and the US-Mexico Border in the New Era of Heightened Nativism (Lexington Books 2020).

36Shoshana Fine and José Ignacio Torreblanca, Border Games: Has Spain found an Answer to the Populist Challenge on Migration? (Policy Briefs, ECFR 2019).

REFERENCES

-

Amit K and Riss I, ‘The Role Of Social Networks in the Immigration Decision-Making Process: The Case of North American Immigration to Israel’ (2007) 25(3) Immigrants & Minorities 290, doi:10.1080/02619280802407517.

-

Ashby NJ, Bueno A and Villarreal DM, ‘The Determinants of Immigration from Mexico to the United States: A State-to-State Analysis’ (2013) 20(7) Applied Economics Letters 638, doi:10.1080/13504851.2012.727964.

-

Aziz N, Chowdhury M and Cooray A, ‘Why do People from Wealthy Countries Migrate?’ (2022) 73(C) European Journal of Political Economy 102, doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102156.

-

Boubtane E, Coulibaly D and Rault C, ‘Immigration, Unemployment and GDP in the Host Country: Bootstrap Panel Granger Causality Analysis on OECD Countries’ (2013) 33(C) Economic Modelling 261, doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.04.017.

-

Carella M, Gurrieri AR and Lorizio M, ‘The Role of Non-Profit Organisations in Migration Policies: Spain and Italy Compared’ (2007) 36(6) The Journal of SocioEconomics 914, doi:10.1016/j.socec.2007.08.001.

-

Carty V, The Immigration Crisis in Europe and the US-Mexico Border in the New Era of Heightened Nativism (Lexington Books 2020).

-

Cobb-Clark DA, ‘Incorporating US Policy into a Model of the Immigration Decision’ (1998) 20(5) Journal of Policy Modelling 621, doi:10.1016/S0161-8938(97)00064-1.

-

Dodson ME(III), ‘Welfare Generosity and Location Choices Among New United States Immigrants’ (2001) 21(1) International Review of Law and Economics 47, doi:10.1016/S0144-8188(00)00040-5.

-

Emilsson H, ‘Who Gets in and Why? The Swedish Experience with Demand-Driven Labour Migration - Some Preliminary Results’ (2014) 4(3) Nordic Journal of Migration Research 134, doi:10.2478/njmr-2014-0017.

-

Facchini G, Margalit Y and Nakata H, ‘Countering Public Opposition to Immigration: The Impact of Information Campaigns’ (2022) 141(C) European Economic Review 103959, doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103959.

-

Fine S and Torreblanca JI, Border Games: Has Spain found an Answer to the Populist Challenge on Migration? (Policy Briefs, ECFR 2019).

-

Fischer AM, ‘Immigrant Language Barriers and House Prices’ (2012) 42(3) Regional Science and Urban Economics 389, doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.11.003.

-

Godenau D, ‘Irregular Maritime Immigration in the Canary Islands: Externalization and Communautarisation in the Social Construction of Borders’ (2014) 12(2) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 123, doi:10.1080/15562948.2014.893384.

-

González L and Ortega F, ‘How do Very Open Economies Adjust to Large Immigration Flows? Evidence from Spanish Regions’ (2011) 18(1) Labour Economics 57, doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2010.06.001.

-

Grau Grau AJ and Ramírez López F, ‘Determinants of Immigration in Europe. The Relevance of Life Expectancy and Environmental Sustainability’ (2017) 9(7) Sustainability 1093, doi:10.3390/su9071093.

-

Hu Z and others, ‘Longing for the Blue Sky: Urban Air Quality and the Individual Decision to Immigrate’ (2022) 79 Journal of Asian Economics 101437, doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101437.

-

Klimaviciute L and others, ‘The Impact of Brexit on Young Poles and Lithuanians in the UK: Reinforced Temporariness of Migration Decisions’ (2020) 9(1) Central and Eastern European Migration Review 127, doi:10.17467/ceemr.2020.06.

-

Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė V and others, Migration Culture: A Comparative Perspective (Springer Cham 2021) doi:10.1007/978-3-030-73014-7.

-

Lewer JJ and Van den Berg H, ‘A Gravity Model of Immigration’ (2008) 99(1) Economics Letters 164, doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2007.06.019.

-

Mendoza C, ‘The Role of the State in Influencing African Labour Outcomes in Spain and Portugal’ (2001) 32(2) Geoforum 167, doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00053-6.

-

Moreno-Fuentes FJ, ‘Migrants’ Access to Social Protection in Spain’ in JM Lafleur and D Vintila (eds), Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond vol 1 (Springer Cham 2020) 405, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-51241-5_27.

-

Naval J, ‘Wealth Constraints, Migrant Selection, and Inequality in Developing Countries’ (2019) 23(2) Macroeconomics Dynamics 535, doi:10.1017/S1365100516001255.

-

Oigenblick L and Kirschenbaum A, ‘Tourism and Immigration: Com-Paring Alternative Approaches’ (2002) 29(4) Annals of Tourism Research 1086, doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00023-3.

-

Ródenas C, Martí M and León Á, ‘A New Pattern in International Mobility? The Case of Spain in the Great Crisis’ (2017) 76(299) Investigación económica 153, doi:10.1016/j.inveco.2017.02.003.

-

Săseanu AS and Petrescu RM, ‘Education and Migration. The Case of Romanian Immigrants in Andalusia, Spain’ (2012) 46 Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 4077, doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.201.

-

Segal UA, Mayadas NS and Elliott D, ‘A Framework for Immigration’ (2006) 4(1) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 3, doi:10.1300/J500v04n01_02.

-

Sekiguchi T and others, ‘The Effects of Differences in Individual Characteristics And Regional Living Environments on the Motivation to Immigrate to Hometowns: A Decision Tree Analysis’ (2019) 9(3) Applied Sciences-Basel 2748, doi:10.3390/app9132748.

-

Young Y, Loebach P and Korinek K, ‘Building Walls or opening Borders? Global Immigration Policy Attitudes Across Economic, Cultural and Human Security Contexts’ (2018) 75 Social Science Research 83, doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.006.

-

Zapata-Barrero R, ‘Perceptions and Realities of Moroccan Immigration Flows and Spanish Policies’ (2008) 6(3) Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 382, doi:10.1080/15362940802371697.

Authors information

Tetiana Zatonatska

Doctor of Economic Sciences, Professor, Department of Economic Cybernetics, Faculty of economics, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine tzatonatska@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9197-0560

Tetiana Zatonatska

Doctor of Economic Sciences, Professor, Department of Economic Cybernetics, Faculty of economics, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine tzatonatska@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9197-0560

Yulia Forostiana

Student, Department of Economic Cybernetics, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine yulia.forostiana@knu.ua https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0301-6617

Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis

Dr., Professor, Department of the Theoretical Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business administration, Vilnius University, Lithuania vincas.giedraitis@evaf.vu.lt https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0293-0645

Yana Fareniuk

Ph. D. (Economics), Department of Economic Cybernetics, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine yfareniuk@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6837-5042

Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Ph. D. (Economics), SESE «Academy of Financial Management», Ukraine dzatonat@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4828-9144

Corresponding author, solely responsible for the manuscript preparing

Conceptualization - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Data curation - Yulia Forostiana, Yana Fareniuk

Formal Analysis - Yulia Forostiana, Yana Fareniuk

Funding acquisition - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yulia Forostiana, Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis,

Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Investigation - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yulia Forostiana, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Methodology - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Project administration - Tetiana Zatonatska

Resources - Yulia Forostiana, Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis

Software - Yulia Forostiana, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Supervision - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yana Fareniuk

Validation - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yana Fareniuk

Visualization - Yulia Forostiana, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Writing – original draft - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yulia Forostiana, Vincentas Rolandas

Giedraitis, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Writing – review & editing - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yulia Forostiana, Vincentas Rolandas

Giedraitis, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Competing interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Disclaimer: The author declares that her opinion and views expressed in this manuscript are free of any impact of any organizations.

About this article

Cite this article Zatonatska T, Forostiana Yu, Giedraitis VR, Fareniuk Ya and Zatonatskiy D, ‘Impact Factors for Immigration to Spain’ (2024) 7(1) Access to Justice in Eastern Europe 264-84 https://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18-7.1-a000119

Submitted on 14 November 2023 / Revised 4 December 2023 / Approved 08 January 2024

Published: 1 February 2024

DOIhttps://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18-7.1-a000119

Managing editor – Dr. Ganna Kharlamova. English Editor – Julie Bold.

Summary: 1. Introduction. – 2. Literature Review. – 2.1. Social Factors. – 2.2. Economic Factors. – 2.3. Political Factors. – 2.4. Legal Factors. – 3. Methods. – 4. Results: Modelling and Forecasting. – 5. Conclusion.

Keywords:immigration, econometrics, Spain, employment, social-economic indicators. JEL: F22, O15, C01

Rights and Permissions

Copyright: © 2024 Tetiana Zatonatska, Yulia Forostiana, Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis, Yana Fareniuk and Dmytro Zatonatskiy. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

About Authors

Tetiana Zatonatska

Dmytro Zatonatskiy

Conceptualization - Tetiana Zatonatska, Yana Fareniuk, Dmytro Zatonatskiy

References

Reviews for article

Add a Review