1. Introduction. — 2. Evolution of human organ trafficking. — 3. Crime which is committed from before birth to after death. — 4. The current nexus between human organ trafficking, business, and poverty. — 5. Human organ trafficking rise as a major human rights issue. — 6. Conclusions.

ABSTRACT

Background:The trafficking of human organs has evolved over the years. At first it appeared across isolated cases, but over time it has increased the curiosity of organised crime due to the high benefits and the small possibility of the perpetrators being pursued with an international character. The perpetrators of this criminal act start this criminal activity with the trafficking of sperm, but they can also continue with the tissues and organs from corpses. Also, human rights have evolved in recent decades. Today, human rights are at the epicentre of global politics. In addition, security issues, poverty, social inequality, non-respect of human rights, lack of adequate laws, and lack of law enforcement are prerequisites for a particular impact on the trafficking of human organs.

Methods:This paper provides a comparative look at the topic with a special emphasis on human organ trafficking by analysing in different and interrelated perspectives, including the social aspect, criminal aspect, the benefits of criminal groups, and the violation of basic human rights.

Results and conclusions:As part of the concluding remarks, suggestions for future actions by law enforcement institutions in terms of anti-trafficking policies and practices.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human organ trafficking has economic, business, and societal origins stemming from before the birth of a person until after death. Recently, in the stage of world politics, human rights, trafficking of human organs, poverty, and inequality have taken on another dimension because the crises that affected most of the world were different and attacked in different ways. These crises, namely, poverty, political destabilisation, corruption, isolation, organised crime, nepotism, and fear of various conflicts, pose a threat to general security.

Trafficking in human organs is a multidimensional phenomenon with broad domestic, transnational, regional, and global expansion. As such, it requires a national, regional, and international approach to combat this phenomenon. Moreover, over the last decade or so, the comprehensive treatment of human organ trafficking has entered the agenda of the multilateral and bilateral international organisations, but also by developed countries as an interdisciplinary strategy. Firstly, this essay will address the evolution of human organ trafficking from the point of view of its spread as a negative social phenomenon of transnational character. Next, we will tackle the relationship between trafficking and crime. Third, we will analyse the current nexus between human organ trafficking, business, and poverty. Finally, we will discuss human organ trafficking rise as a major human rights issue.

2 EVOLUTION OF HUMAN ORGAN TRAFFICKING

Many forms of human exploitation are known throughout human history. In this context, slavery and human trafficking were the most brutal and shocking forms of human rights, but these forms have changed globally, since the first sale of human organs for transplantation was reported in the 1980s when poor Indians sold their organs to foreign patients.1 India was a common country that exported organs, however, in order to prevent this phenomenon of buying and selling organs, the Organ Transplantation Act was passed, thereby reducing the number of transplants. This did not stop the trade as the underground organ market still exists in India. Unfortunately, according to the association of health volunteers, every year, 2,000 Indians sell their kidneys.2 Also, during 1984-1988, hundreds of patients from the United Arab Emirates and Oman voluntarily travelled to Bombay to purchase kidneys from unrelated Indian donors for $2,600-3,300. They used the mediation of local borkers, which means Indian brokers.3

Not even European countries were protected in terms of this negative phenomena. As far as Europe is concerned, evidence exists of EU citizens traveling abroad to get organs. The British Medical Journal, in 1996, described two German patients who died from complications after a transplant performed in India. It is stated that at least 25 German patients received kidneys abroad. The article called for appropriate legislative measures to prevent such incidents.4

Organ trafficking is only increasing over time. This is best proven by Nancy Scheper-Hughes, chair of Berkeley’s doctoral program in medical anthropology and director of Organs Watch, a research-documentation centre in California. Scheper-Hughes told CNN that the market for human organs is booming so that “Demand for fresh organs and tissue . . . is insatiable.” She added that fresh kidneys from “brain death,” or those that have been lost with the help of trained organ harvesters, are the blood diamonds of illegal and criminal trafficking.5 In this sense, it is worth noting that human organ trafficking has increased in some countries due to the violation of human rights. For example, in March of 2006, a woman revealed that about 4,000 Falun Gong practitioners had been killed for their organs at the hospital where she worked. A week later, a Chinese military doctor not only confirmed the woman’s claims but claimed that such horrors took place in 36 different concentration camps across the country.6 In July 2006, former Canadian Secretary of State for Asia and the Pacific, David Kilgour, and renowned human rights lawyer, David Matas, released their report in which they reached the “sad conclusion that the allegations are true.” After this, two books were published on the subject, Bloody Harvest: Harvesting the Organs of Falun Gong Practitioners in China (2009) and State Organs: Transplant Abuse in China (2012). They conclude that tens of thousands Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs.7 According to public reports, before 1999, a total of approximately 30,000 organ transplants were performed in China. In just the six-year period from 1994 to 1999, approximately 18,500 organ transplants were completed. ShiBingyi, vice president of the Chinese Medical Organ Transplant Association, stated that by 2005, a total of about 90,000 transplants, with around 60,000 transplants occurring in the six-year period from 2000 to 2005, had taken place after the persecution of Falun Gong began.8

Trafficking in human organs covers an even wider range. The International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE), with former prisoners and victims of ISIL, also illuminates the potential use of war criminals in this realm, including for financial purposes. One of the respondents, Abo Reed, a former ISIL surgeon, said that these surgeons removed the kidneys and corneas of prisoners and told him that “jihadists are more deserving than organs.” In December 2015, a former ISIL fighter stated, “Now we have a statement from Da’esh: From now on do not kill slaves. Surely we should use their bodies to make money [for organ trafficking]. Basically, they are saying that the slaves are already ‘dead.’ We have to make money from their bodies by selling body parts.”9 Also, in February 2015, Iraqi Ambassador Mohamed Alhakim asked the UN Security Council to investigate the deaths of twelve doctors in Mosul, Iraq, who he claimed were killed by ISIS after they refused to remove organs from dead bodies. He also claimed that some of the bodies they found were mutilated by an opening in the back where the kidneys were located. “This is definitely something bigger than we think,” said Ambassador Alhakim.10

We believe that in the historical review, human organ trafficking should be divided into two phases: the first phase encompasses the period when individuals performed illegal organ transplants for personal needs (above facts-data), and the second phase began when human organs were searched for online and the participants became organised criminal groups, or when trafficking in human organs was facilitated through intermediaries, brokers, and healthcare workers who organise trips and recruit donors. In the second phase, human organs started to be treated as commodities in order to give members of organised crime groups as much financial gain and power as possible. Trafficking in human organs has been a form of crime since ancient times. It is important to note that this trend gradually changed at the beginning of the XXI century when organised criminal groups engaged in organ trafficking. That is, when human organ trafficking began to be commercialised, and the illegal market for human organs flourished. This illegal market is a point of contact where, on one side, hopeless patients and poor individuals meet with a mediator, and on the other side are criminals who use these circumstances to make money on other people’s troubles.

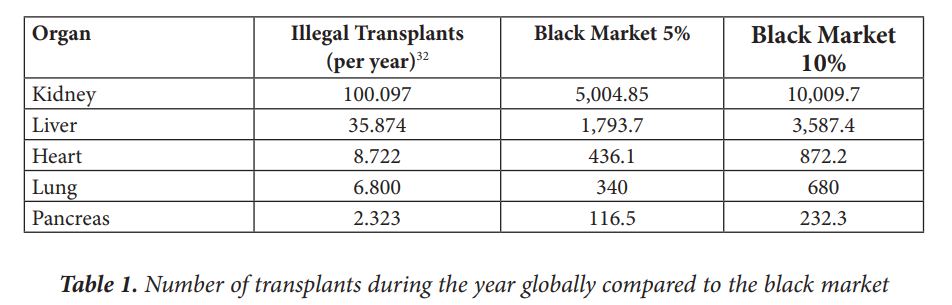

In 2019, the most common organ for transplant was the kidney, with a global estimate of 100,097. Following are the liver (35,874), heart (8,722), lung (6,800), and pancreas (2,323).11

In comparative terms, these phases provide different data on trafficking in human organs. In the first phase, there were rare and isolated cases. The second phase unfortunately changed the status quo as trafficking in human organs is a serious problem today, in the same regions and beyond. Given the facts above, we believe that in the second phase, the growth of trafficking in human organs was huge compared to the first phase. The second phase switched to the trafficking of human organs due to the great benefits for organised crime members. In addition, this negative social phenomenon at this stage of development attacks some jurisdictions.12

This fact is based on the conclusion of the Council of Europe, which established that in recent years, there has been an increase in transplant tourism and trafficking in human organs around the world.13

3 CRIMES COMMITTED FROM BEFORE BIRTH TO AFTER DEATH

Global market capitalism, together with medical and biotechnological advances, has stimulated new tastes and desires for skin, bones, blood, organs, tissues, marrow, reproductive, and genetic material from others. In these new transactions, the human body is radically transformed.14 In such circumstances, two distinct individuals are needed: recipients and organ donors. Altruism for organ donation is not lacking, but unfortunately, the number of recipients is much higher than the number of donors. Today, there is a large gap between organ recipients, transplants performed, and organ donors on an annual basis in one country. This fact also carries great risks because it gives opportunities for “criminal traffickers” to abuse human organs from people who hope to continue their lives and victims who have no hope, left without a choice but to sell their organs.

This type of crime does not recognise the age, gender, nationality, or religion of these victims because there is a widespread sale. In this sense, the trafficking of human organs is carried out from before birth, which means that sperm banks have been invented across the globe and work in a similar way as virtual supermarkets. Their goods are displayed on their websites; each donor “for sale” is described by bank staff and as a self-introduction where they are asked to provide information in response to various questions about personality, hobbies, educational and professional achievements, future plans, likes and dislikes, etc.15

Also, an expanded type of organ sale, i.e., renting, is the transplantation of foetuses to so-called “surrogate mothers.” The cost of surrogacy, in the case of a healthy birth, ranges between $10,000 and $40,000 (and in the case of a failed birth, only about $1,000). To date, such contracts between contractual parents and leased uterus owners, over 5,000 babies were born in the United States alone. The cash turnover from contracts entered by contract parents, surrogate mothers, and brokers was around $40 million in 1990, excluding amounts paid by contract parents to brokers when contracts were not fulfilled.16

Society has always reacted to aggression against life and body, of course, depending on their reciprocal relationships. Organised criminal groups, i.e., organ traffickers, use different ways and methods to reach the desired organs. In this regard, there are concerns about the discovery of a brain death machine identified in an investigative process conducted by investigative journalists presented in the documentary. One researcher said, “This machine causes brain death, but other organs remain undamaged.”17 The brain death machine causes the immediate death of the human brain. In terms of its structure, it contains a gas gun with a high speed. Inside, a metal ball is placed that hits the main stem of the human brain and causes immediate brain death.18

A brain death machine19 does not require special properties for use and production, but can unfortunately cause brain death in an incredibly short time. According to the patent, this machine does not damage other vital organs, i.e., organs that are highest in demand for transplantation or organs that are the object of trade, so vital organs remain healthy. The way it works and its consequences should be of primary concern to state institutions dealing with the fight against trafficking in human organs.

Of course, when one considers that murder can be committed in different ways, there are different motives for this, including murder to remove organs from corpses or various exhibitions with parts of the human body.

For example, between 1976 and 1991, the Montes de Oca Institute of Mental Health in Buenos Aires killed patients for organ sales, leading to around 1,400 cases of mysterious disappearances reported during that period. When some of these patients’ bodies were found, 11 doctors from that hospital were arrested.20

A scandal erupted at a general hospital in Ukraine when it was revealed that prominent surgeons there sold the organs of victims of traffic accidents. They received $4,000 in compensation for their efforts, the equivalent of several Ukrainian annual salaries. Some of the victims were not clinically dead when the surgeons stuck their scalpels into them.21

With this begins the theft of corpses, which were then used for trade. Not only that, but with the increase in the demand for the theft of corpses, this phenomenon was also an instigator. It pushed for murder in order to increase the number of corpses available. For over a year, in his apartment in Edinburgh, William Burke killed sixteen victims, all guests, and then sold their bodies to local medical schools.22

In addition to the aforementioned cases of corpse abuse, it is not uncommon for corpse parts to be placed and presented in various exhibitions. Different compounds are used to replace the fluid in the human body during various exhibitions, otherwise known as body plasticisation technology.23 The technology of plasticisation of corpses would not have a large effect and would not be in high demand if it were not exposed all over the globe. In November 2015, in Manhattan, New York, an exhibition was opened with 22 corpses without skin and 260 samples of human organs. In 2006, the American newspaper, The New York Times, reported that the interest to see the exhibition was high and gathered around 20 million viewers. The organisers explained that “no one can know their identity.”24 Unfortunately, Europe also faced this phenomenon. During 2012, 200 human bodies were exhibited in Dublin, the capital of Ireland. Similar exhibits existed in the capital of Hungary, Budapest, where 150 corpses and other human organs were shown, and there were also exhibits of this nature in Czech Republic’s capital. It is worth noting that these were not the only countries where such exhibitions were held. Over 20 countries have shown these types of exhibitions, with the number of visitors across all exhibits reaching 35 million people.25

4 THE CURRENT NEXUS BETWEEN HUMAN ORGAN TRAFFICKING, BUSINESS, AND POVERTY

Trafficking in human organs does not happen if the organ is not treated as a commodity. People who have waited for a long time on waiting lists with good incomes look for the desired organ as soon as possible, regardless of the method. Often, “money” is crucial for organ transplantation. In the classical sense, human organs are purchased and sold on the black market, and unfortunately, they are developing rapidly due to the huge difference in “supply and demand,” i.e., the purchase and sale price of organs. Organ trafficking usually plays a role in the medical economy of poor countries, where it lowers the standards of surgical work, endangers vendors and their families, abuses their rights, opens the possibility of exploiting the rich over the poor, and turns the human body into a commercial commodity. The black market phenomenon attacks the unprotected and disenfranchised, exploiting the most vulnerable sections of the population. The simple answer to these questions is that the sale of organs becomes an act of despair and hopelessness. An individual must not risk his life to save another life, and as such, organ trafficking is illegal while all the money earned via this method is dirty money.26

Trafficking in human organs, along with trafficking in drugs, people, weapons, diamonds, gold, and oil, is rising as the subject of a billion-dollar illegal industry worldwide.27 Global Financial Integrity (GFI), in its 2011 report, estimated that human organ trafficking could generate illicit earnings between $600 million and $1.2 billion a year.28 In fact, of even greater concern is that this assessment states that not all transplants of vital organs were included due to a lack of sufficient data. If all the data for vital organs was available, it is certain that these numbers would be much higher and much more disturbing.29 The data presented by GFI in this report showed the large number of illegal transplants annually worldwide and the associated exorbitant prices on the black market.

According to GFI, between $840 million and $1.7 billion a year are generated from illegal organ trafficking. This estimate refers to the illegal sale of the five best-selling organs: kidneys, liver, heart, lungs, and pancreas. There is a huge difference in the amount of money that organ donors pay and the amount that the recipient receives. For example, the price of kidneys in developed countries is $20,000, while in developing countries it is around $3,000. The difference is more than 500%.30

To establish the above facts, we then must consider the number of transplants globally for each vital organ and the data provided by WHO experts to estimate that 5-10% of all transplants are illegal.31 This then gives us the following data presented in Table 1 regarding illegal organ transplantation, via the black market for human organs.

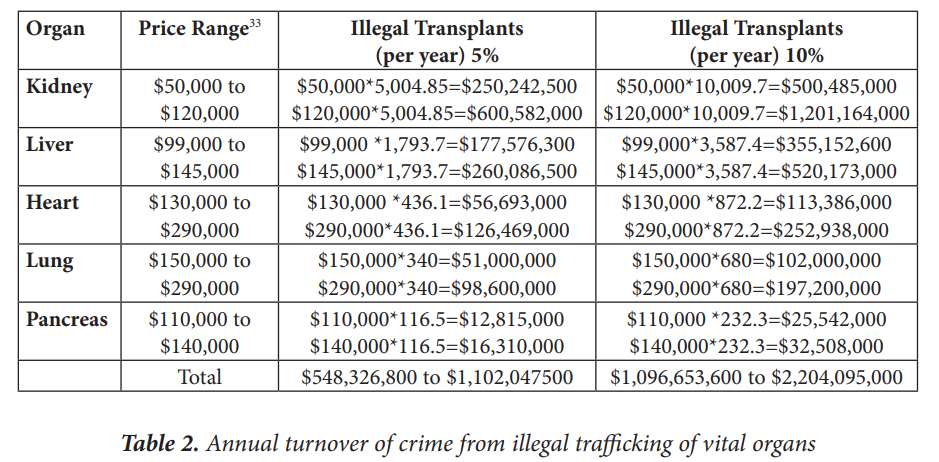

We then multiply the number of organs obtained from the black market by the purchase price on the black market to prove the annual turnover created by the black market through the sale and purchase of vital human organs.

From Table 2, we clearly see that this crime has a high annual turnover globally. If based on just 5% of illegal transplants, this turnover is around $548,326,800 to $1,102.047500; if based on 10% of illegal transplants, this turnover is around $1,096,653,600 to $2,204,095,000. This means that in 2019, there was a higher increase in turnover compared to that of 2011 and 2017.

5 HUMAN ORGAN TRAFFICKING RISES AS A MAJOR HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUE

The United Nations has always promoted the promulgation of Conventions of special importance, which serve as the legal basis for many other conventions approved by other international and national organisations. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has served as a basis for many other conventions, and as such, it also serves in the convention against trafficking in human organs. Therefore, in this section, we will deal with the trafficking of human organs from the point of view of freedoms and human rights, which is always based on the human rights convention.34

Bearing in mind that the commercialisation of the human body (prostitution, pornography) and any other commercialisation of human organs is unacceptable, then the question arises of whether it is natural that people have the right to sell their organs for financial gain.

In this context, it should be considered whether personal freedom can reach beyond collective responsibility. Personal freedom refers to the freedom of each individual towards his life and goals, not accepting the intervention of other individuals.

This is clearly defined Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.35 Although the state guarantees the right to life to every citizen without distinction, citizens are obliged by the state not to risk their lives but to also respect the lives of others.36 Therefore, we believe that individual autonomy is limited in organ trafficking because of this collective responsibility and some ethical claims that the potential harm of organ trafficking exceeds the rights of the individual.

Furthermore, the right to bodily autonomy for the financial gain or commercialism of the human body (prostitution, pornography, organ sales, etc.) is prohibited in religious and legal terms. Unfortunately, organ trafficking has become one of the most important ways to obtain organs in the world today, so we must take a strong stance against it, preventing it from the individual level and on to society as a whole.

Unfortunately, this crime has already established the misuse of corpses to remove organs. However, a petition was filed before the European Court of Human Rights to establish a violation of Article 3 of the Convention, Khadzhialiyev and others v. Russia, no. 3013/04, paragraphs 120-22, dated November 6, 2008. In this regard, the Court pointed out that in the special area of organ and tissue transplantation, it was recognised that the human body must be treated with respect even after death. The Court noted that the rights of organ and tissue donors, whether living or deceased, are protected by the Convention on Human Rights and the Additional Protocol. The aim of these agreements is to protect the dignity, identity, and integrity of “everyone” who is born, whether alive or dead at the time. For the Court, in view of these specific circumstances, the emotional suffering incurred by the applicant constituted degrading treatment contrary to Article 3.37 In this judgment, in the case of Khadzhialiyev and others v. Russia, the Court found that the removal of organs from corpses violated human rights, dignity, identity, integrity, and liberty.

6 CONCLUSION

The trafficking of human organs is a complex crime. In this sense, law enforcement institutions are confronted with wide-ranging problems when following the right path, beginning with the identification of criminal activity, the identification of the trafficking victim, the full investigation of the case, and measures taken to bring the case to court so that the criminal faces deserved punishment.38 Penal policies against this phenomenon should be strict because the consequences of these crimes can be fatal for the victim, and they can cause death or serious damage to physical or mental health. This negative social phenomenon is spreading with great dynamics, showing extraordinary advantages for criminal groups due to the incredibly low risk of criminal prosecution of these perpetrators.39

Bearing what was addressed in mind, the final remarks are fourfold.

First, from the perspective of the evolution of human organ trafficking, it can be concluded that the beginning of the XXI century marked the engagement of organised criminal groups in human organ trafficking, that is, human organ trafficking started its commercialisation, and the illegal human organ market began to grow. Trafficking in human organs is controlled by organised criminal groups almost worldwide, and these criminal groups exploit the mismatch between “supply and demand.

Second, the governments of the states throughout the world’s supply and demand must provide balance. We consider that states should accept the opt-out system, given that countries with presumed consent laws have increased the organ donation rate by 25% to 35% more than in countries with explicit selection laws or an opt-in law.40 This allows for a system without presumed consent, in addition to increasing the rate of organ donation. As such, we believe that a special measure to fight this negative phenomenon, this form of organised crime, is needed. Also, the governments of each European country, must meet the requirements to be members of Eurotransplant, Scandiatransplant, and Balttransplant, and accept the system of presumed consent because it increases the number of potential donors.

Third, we suggest that legitimate businesses, namely private clinics where illegal organ transplants are performed, can play a crucial role in curbing trafficking and other human rights abuses by not allowing transplants to be performed in those clinics and by not supporting the supply trafficking chains. Also, the doctors and other medical support staff who work in these clinics should be addressed as they make the illegal business more profitable

Finally, given the nature of human organ trafficking, there is currently no single coherent summary that can capture different perspectives and integrate them into an article like this. As trafficking is a complex criminal offense, it creates problems that are profoundly multifaceted. While the views and actions are comprehensive, they are also specific and therefore require greater efforts. In preventing trafficking in human organs and developing prevention policies, states should include research and data collection, awareness-raising, public education campaigns, and training programs for potential victims as well as professional staff (each state should identify which health workers are the main actors in organised groups regarding human organ trafficking to aid in this).

1Gabriel M Danovitch and others, ‘Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism: The Role of Global Professional Ethical Standards - the 2008 Declaration of Istanbul’ (2013) 95(11) Transplantation 1306, doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318295ee7d.

2Yosuke Shimazono, ‘The State of the International Organ Trade: A Provisional Picture Based on Integration of Available Information’ (2007) 85(12) Bulletin of the World Health Organization 955, doi: 10.2471/ blt.06.039370.

3AK Salahudeen and others, ‘High Mortality Among Recipients of Bought Living-Unrelated Donor Kidneys’ (1990) 336 The Lancet 725, doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92214-3.

4Helmut Karcher, ‘German Doctors Protest Against “Organ Tourism”’ (1996) 313(7068) British Medical Journal 1282, doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7068.1282a.

5Jan Kalvik, ‘ISIS Defector Reports on the Sale of Organs Harvested from ISIS held “Slaves”’ (Defence and Intelligence Norway, 1 January 2016) https://www.etterretningen.no/2016/01/01/isis-defector-reportson-the-sale-of-organs-harvested-from-isis-held-slaves/ accessed 29 September 2023.

6‘Žetva organa’ (Falun Dafa, 2019) https://hr.minghui.org/categories/102 accessed 29 September 2023.

7‘Najava Kine o obustavljanju žetve organa samo trik: Ubijeni zatvorenici savjesti su glavni izvor organa’ (Faluninfo, 8 December 2014) https://faluninfo.rs/articles/1669 accessed 29 September 2023.

8David Matas and David Kilgour, ‘Bloody Harvest: Revised Report into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China’ (An Independent Investigation Into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China, 31 January 2007) para F 27 https://www.organharvestinvestigation. net/ accessed 29 September 2023.

9Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate, Identifying and Exploring the Nexus between Human Trafficking, Terrorism, and Terrorism Financing (CTED 2019) para 92 https://www.un.org/ securitycouncil/ctc/sites/www.un.org.securitycouncil.ctc/files/files/documents/2021/Jan/ht-terrorismnexus-cted-report.pdf accessed 29 September 2023.

10Kalvik (n 5).

11Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, Organ Donation and Transplantation: Activities 2019 Report (GODT, April 2021) https://www.transplant-observatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ GODT2019-data_web_updated-June-2021.pdf accessed 29 September 2023.

12ibid

13Council of Europe, ‘A New Convention to Combat Trafficking in Human Organs’ (Council of Europe, 8 July 2014) https://rm.coe.int/16807212f2 accessed 29 September 2023.

14Nancy Scheper-Hughes, ‘Heo-Cannibalism: The Global Trade in Human Organs’ (2001) 3(2) The Hedgehog Review Offers Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/ the-body-and-being-human/articles/neo-cannibalism-the-global-trade-in-human-organs accessed 29 September 2023.

15Ya’arit Bokek-Cohen, ‘Becoming Familiar with Eternal Anonymity: How Sperm Banks use Relationship Marketing Strategy’ (2014) 18(2) Consumption Markets and Culture 155, doi: 10.1080/10253866.2014.935938.

16Darko Polšek, Zapisi Iz Treće Kulture (Naklada Jesenski i Turk 2008) 92.

17TV Chosun, ‘The Dark Side of Transplant Tourism in China: Killing to live’ (17 November 2017) https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=xUiuVjX2ubQ&t=626s accessed 29 September 2023.

18Jason Lee, ‘“Killing to Live”: China Transplant Tourism Exposed by Undercover Journalists’ [2019] Vibrant Dot https://vibrantdot.co/killing-to-live-china-transplant-tourism-exposed-by-undercoverjournalists/ accessed 29 September 2023.

19ibid.

20Polšek (n 16) 89.

21Ana Ursić, Marina Barić i Tajana Umnik, ‘Trgovanje ljudskim organima’ (2006) 14 (1) Kriminologija & socijalna integracija 105.

22David E Jefferies, ‘The Body as Commodity: The Use of Markets to Cure the Organ Deficit’ (1998) 5(2) Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 621.

23David Kilgour, Ethan Gutmann and David Matas, ‘Bloody Harvest / The Slaughter: An Update’ (International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China, 22 June 2016, Revised 30 April 2017) 379 https://endtransplantabuse.org/an-update/ accessed 29 September 2023.

24ibid 378.

25ibid 381.

26Hajrija Mujović-Zornić, Donacija i transplantacija organa (Institut društvenih nauka 2013) 1-10.

27Violeta Besirevic and others, Improving the Effectiveness of the Organ Trade Prohibition in Europe: Recommendations (EULOD 2012).

28Jeremy Haken, Transnational Crime in the Developing World (Global Financial Integrity 2011) 22.

29ibid.

30Channing May, Transnational Crime and the Developing World (Global Financial Integrity 2017) XII, 108.

31United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Trafficking in Persons for the Purpose of Organ Removal: Assessment Toolkit (UN 2015) 11.

32Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (n 11).

33May (n 30) 53-9.

34Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted 10 December 1948 UNGA Res 217 A(III)) https:// www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights accessed 29 September 2023; Council of Europe Convention against Trafficking in Human Organs (25 March 2015) https://www.coe.int/en/ web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=216 accessed 29 September 2023.

35Art. 3 “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person”.

36KK Ghai, ‘Relation between Rights and Duties’ (Your Article Library, 2022) https://www.yourarticlelibrary. com/essay/law-essay/relation-between-rights-and-duties/40374 accessed 29 September 2023.

37Khadzhialiyev and Others v Russia App no 3013/04 (ECtHR, 6 November 2008) para 120-22 https:// hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-89348 accessed 29 September 2023; European Court of Human Rights, Annual Report 2015 (ECHR 2016) 100.

38Fejzi Beqiri, ‘Comparative Analysis of the Criminal Offence of the Trafficking of Human Organs in the Recently-Formed Countries of the Balkans’ (2019) 22(1) SEER Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Eastern Europe 105, doi: 10.5771/1435-2869-2019-1-105.

39Fejzi Beqiri, ‘Trgovanje ljudima u svrhu uklanjanja organa na Kosovu’ (2020) 28(1) Kriminologija & socijalna integracija 78, doi: 10.31299/ksi.28.1.4.

40Abdulwasiu B Popoola and Isyaku Umar Yarube, ‘An Overview of Transplant Tourism: “Kidney Business?”’ (2016) 1(1) Bayero Journal of Biomedical Sciences 104.

REFERENCES

-

Beqiri F, ‘Comparative Analysis of the Criminal Offence of the Trafficking of Human Organs in the Recently-Formed Countries of the Balkans’ (2019) 22(1) SEER Journal for Labour and Social Affairs in Eastern Europe 105, doi: 10.5771/1435-2869-2019-1-105

-

Beqiri F, ‘Trgovanje ljudima u svrhu uklanjanja organa na Kosovu’ (2020) 28(1) Kriminologija & socijalna integracija 78, doi: 10.31299/ksi.28.1.4

-

Besirevic V and others, Improving the Effectiveness of the Organ Trade Prohibition in Europe: Recommendations (EULOD 2012)

-

Bokek-Cohen Y, ‘Becoming Familiar with Eternal Anonymity: How Sperm Banks use Relationship Marketing Strategy’ (2014) 18(2) Consumption Markets and Culture 155, doi: 10.1080/10253866.2014.935938

-

Danovitch GM and others, ‘Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism: The Role of Global Professional Ethical Standards - the 2008 Declaration of Istanbul’ (2013) 95(11) Transplantation 1306, doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318295ee7d

-

Ghai KK, ‘Relation between Rights and Duties’ (Your Article Library, 2022) https://www. yourarticlelibrary.com/essay/law-essay/relation-between-rights-and-duties/40374 accessed 29 September 2023

-

Haken J, Transnational Crime in the Developing World (Global Financial Integrity 2011)

-

Jefferies DE, ‘The Body as Commodity: The Use of Markets to Cure the Organ Deficit’ (1998) 5(2) Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 621

-

Karcher H, ‘German Doctors Protest Against “Organ Tourism”’ (1996) 313(7068) British Medical Journal 1282, doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7068.1282a

-

Kilgour D, Gutmann E and Matas D, ‘Bloody Harvest / The Slaughter: An Update’ (International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China, 22 June 2016, Revised 30 April 2017) https:// endtransplantabuse.org/an-update accessed 29 September 2023.

-

Lee J, ‘“Killing to Live”: China Transplant Tourism Exposed by Undercover Journalists’ [2019] Vibrant Dothttps://vibrantdot.co/killing-to-live-china-transplant-tourism-exposed-by-undercoverjournalists accessed 29 September 2023

-

Matas D and Kilgour D, ‘Bloody Harvest: Revised Report into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China’ (An Independent Investigation into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China, 31 January 2007) para F27 https://www. organharvestinvestigation.net accessed 29 September 2023

-

May C, Transnational Crime and the Developing World (Global Financial Integrity 2017)

-

Mujović-Zornić H, Donacija i transplantacija organa (Institut društvenih nauka 2013)

-

Polšek D, Zapisi Iz Treće Kulture (Naklada Jesenski i Turk 2008).

-

Popoola AB and Isyaku Umar Yarube, ‘An Overview of Transplant Tourism: “Kidney Business?”’ (2016) 1(1) Bayero Journal of Biomedical Sciences 104

-

Salahudeen AK and others, ‘High Mortality Among Recipients of Bought Living-Unrelated Donor Kidneys’ (1990) 336(8717) The Lancet 725, doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92214-3

-

Scheper-Hughes N, ‘Heo-Cannibalism: The Global Trade in Human Organs’ (2001) 3(2) The Hedgehog Review Offers Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture https://hedgehogreview. com/issues/the-body-and-being-human/articles/neo-cannibalism-the-global-trade-inhuman-organs accessed 29 September 2023

-

Shimazono Y, ‘The State of the International Organ Trade: A Provisional Picture Based on Integration of Available Information’ (2007) 85(12) Bulletin of the World Health Organization 955, doi: 10.2471/blt.06.039370

-

Ursić A, Barić M i Umnik T, ‘Trgovanje ljudskim organima’ (2006) 14 (1) Kriminologija & socijalna integracija 101

Authors information

Fejzi Beqiri

Assistant Professor, Ph.D., Faculty of Law, Universum International College, Pristina, Republic of Kosova fejzi.k.beqiri@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6404-768X

Co-author, responsible for writing and data curation.

Elda Maloku

Phd.cand., Department of Criminal Law,Faculty of Law, University of Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina malokuelda@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8856-2005

Corresponding author, responsible for conceptualization and methodology.

Ahmet Maloku

Associate Professor, Ph.D., Department of Criminal Law, Faculty of Law, University for Business and Technology, Pristina, Republic of Kosova maloku.ahmet@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1913-4303

Co-author, responsible for writing and data curation.

About this article

Cite this article Fejzi Beqiri, Elda Maloku and Ahmet Maloku, ‘Human Organs Trafficking: Perspective from Criminal Matters, Business and Human Rights’ (2023) 4(21) Access to Justice in Eastern Europe. https://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18- 6.4-a000489

Submitted on 23 Sep 2023 / Revised 12 Oct 2023 / Approved 20 Oct 2023

Published: 1 Nov 2023

DOIhttps://doi.org/10.33327/AJEE-18-6.4-a000489

Managing editor – Mag. Polina Siedova.English Editor – Nicole Robinson.

Summary: 1. Introduction. — 2. Evolution of human organ trafficking. — 3. Crime which is committed from before birth to after death. — 4. The current nexus between human organ trafficking, business, and poverty. — 5. Human organ trafficking rise as a major human rights issue. — 6. Conclusions.

Keywords: trafficking with human organs, security-crime, brokers, human rights.

Rights and Permissions

Copyright:© 2023 Fejzi Beqiri, Elda Maloku, Ahmet Maloku. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.